Uncomfortable climate

Retreating Arctic ice and a bushfire-ravaged North America are just two indicators of our changing climate.

A northern summer capable of melting virtually all of the Arctic’s floating sea ice was something scientists knew was on the cards in the near future. But many had pegged the likelihood of this occurring in the mid-century at the earliest.

A new study, however, suggests this could occur as soon as the early 2030s – less than a decade away, in other words.

Published in Nature, the peer-reviewed findings also suggest that this milestone could materialise even if nations manage to slow greenhouse gas emissions more decisively. Earlier projections suggested quick action might preserve the ice.

“We are very quickly about to lose the Arctic summer sea-ice cover, basically independent of what we are doing,” says climate scientist Dirk Notz from Germany’s University of Hamburg, and one of the new study’s authors. “We’ve been waiting too long now to do something about climate change to still protect the remaining ice.”

Sea ice has dwindled in recent decades, but the consequences of a lack of summer ice will have consequences far beyond the region.

Sea ice reflects solar radiation back into space. The less ice there is, the faster the Arctic warms. This causes the Greenland ice sheet to melt more quickly, adding to sea-level rise globally.

“We are very quickly about to lose the Arctic summer sea-ice cover, basically independent of what we are doing”

Arctic amplification

Over the past 40 years, the far north has already been warming four times as quickly as the global average, a phenomenon scientists refer to as “Arctic amplification”.

“Our result suggests that the Arctic amplification will be coming faster and stronger,” says climate scientist Seung-Ki Min from South Korea’s Pohang University of Science and Technology and also author of the Nature paper. “That means the related impacts will be also coming faster.”

Icy patches are expected to remain in certain corners of the Arctic for some time to come, with the threshold scientists use being one million km2 of ice. This is less than 15 per cent of the Arctic’s seasonal minimum ice cover in the late 1970s.

Smoke in North America

At least 400 bushfires burning across Canada in early June prompted air pollution warnings across North America. The smoke hovered over major cities in Canada such as Toronto and the northern US.

In New York City, the air quality was the worst since the Environmental Protection Agency began measurements in 1999.

It’s not unusual for bushfires in Canada to burn large sections of forest and grassland each year between May and September. But the 2023 fires scorched an area 10 times larger than usual.

It’s not unusual for bushfires in Canada to burn large sections of forest and grassland each year between May and September. But the 2023 fires scorched an area 10 times larger than usual.

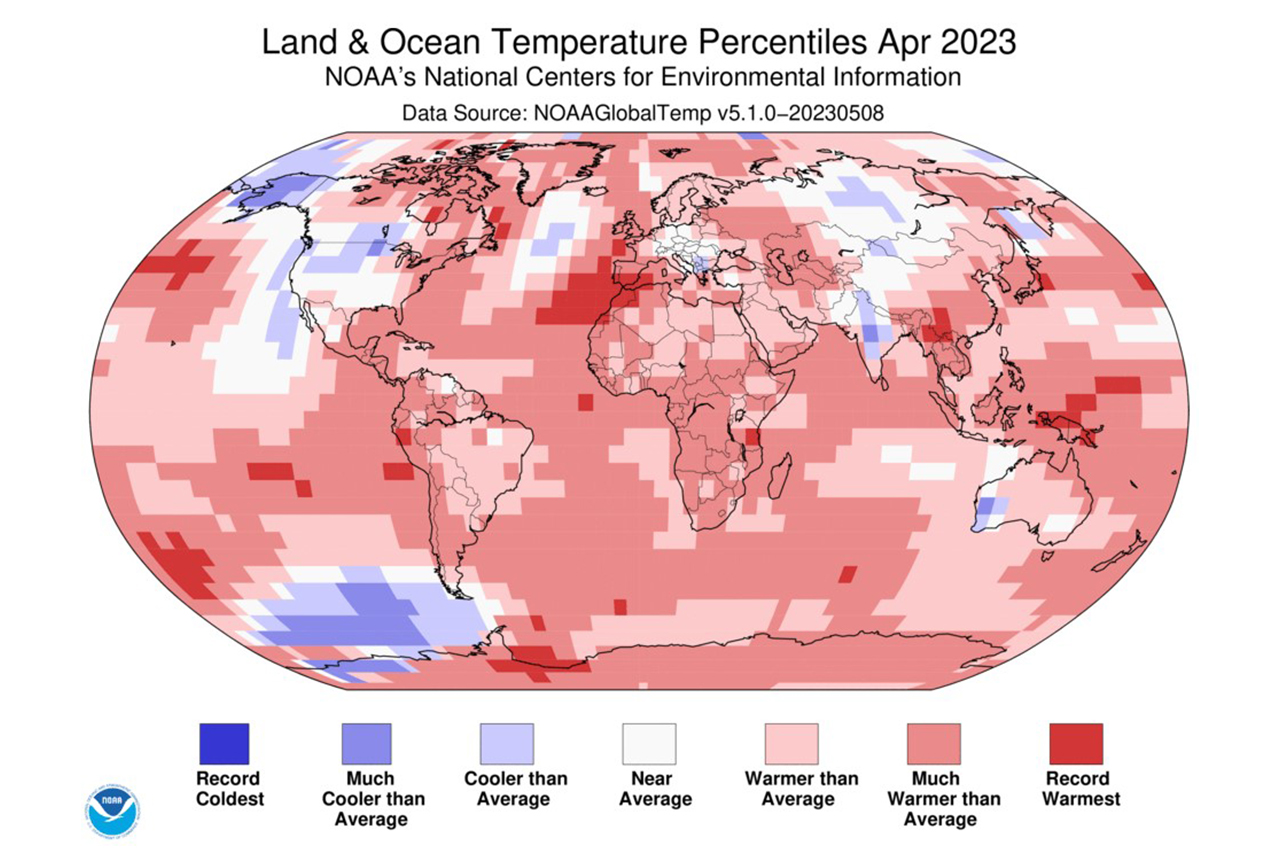

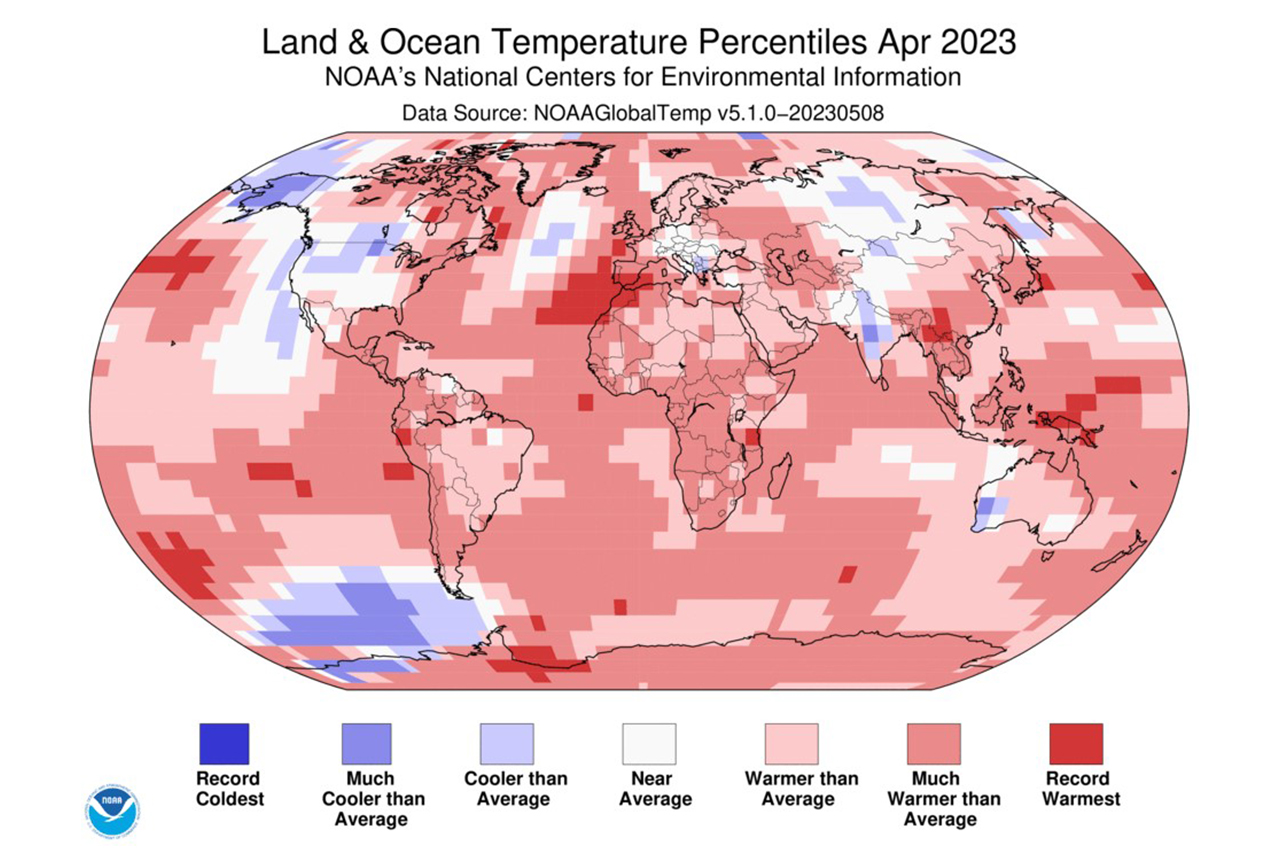

A hot start

April 2023 was the fourth hottest April globally since modern recordkeeping began in 1880, measuring at 1.00°C above NASA’s 1951–1980 baseline average. The six hottest Aprils on record have occurred since 2016.

The US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the European Copernicus Climate Change Service also reported April as being the world’s fourth hottest on record.

Global ocean temperatures experienced their warmest April on record, according to the NOAA. This marked the second-highest monthly ocean temperature for any month on record, just 0.01°C shy of the record-warm ocean temperatures set in January 2016.

The substantial ocean heat helped push the southern hemisphere to its warmest month on record, beating the previous record set in March 2016 by 0.06°C.

Like to know more?

To read the Nature study, go to www.nature.com/articles/s41467-023-38511-8.

This article appears in Ecolibrium’s June-July 2023 edition

View the archive of previous editions

Latest edition

See everything from the latest edition of Ecolibrium, AIRAH’s official journal.