Learning to thrive

A research centre at Queensland University of Technology has set out an ambitious range of projects to build our knowledge of indoor air quality.

As Australia gradually wakes up to the immense opportunity of improving indoor air quality, research and pilot projects will play a critical role in building evidence and momentum. The ARC Training Centre for Advanced Building System against Airborne Infection Transmission (THRIVE), hosted by the Queensland University of Technology, is home to many such projects.

AIRAH Advocacy and Policy Manager Mark Vender caught up with Centre Director, Distinguished Professor Lidia Morawska, to discuss the latest developments in the IAQ space.

Mark Vender: We’ve seen more engagement from government lately on the topic of IAQ with the publication of a National Science and Technology Council (NTSC) report, and research funding from the Victorian government. Is the topic gaining traction?

Lidia Morawska: Each of these activities is very important from a different point of view.

The NTSC report is not a recommendation – that was very clearly stated by the Chief Scientist. It is compound information about the impact specifically of infection transmission in buildings, demonstrating that there is knowledge about this, and also that there are technologies in place which could be used to lower infection transmission.

We need to do this in the context of a system, because we cannot try to fix one problem without looking at the system. People often use terms like “easy”, “simple” or “low-hanging fruit”, but buildings are complex systems. So the NTSC report was specifically focused on infection transmission, in the context of a system.

The project in Victoria could be called a demonstration project. The idea is to look at a number of different types of public buildings to understand the status quo in terms of indoor air quality; first of all to demonstrate how it can be measured, and secondly, if monitoring shows there are problems, the next step is demonstrating the pathway to fixing these problems.

Of course, this is just a very small subset of buildings, but demonstrating that something like this can be done, as well as the issues and learnings, will be very important.

There’s also another project going on in Victoria: Elucidar. This looks at using germicidal ultraviolet light (GUV) in aged-care facilities. It is a randomised control trial and it’s important from another angle because here we are looking specifically at one technology, which is GUV, but looking at it in a very detailed way.

There’s much more information about the impact of using filtration devices, whether HVAC systems or standalone filter-based air purifiers. This is in some ways a “simple science” – it’s just how much air is going through the device and the filtration efficiency.

GUV is more complex, particularly if we are talking about an upper-room GUV, when it’s not where the pathogens are. We’ve got to rely on these pathogens being taken by air movement to this range and spending enough time there to be inactivated, and also managing the light intensity so that it doesn’t cause other problems.

At the NTSC report launch, the team spoke about the report providing a foundation on which other projects can build more information. What can THRIVE do to move things forward, and what are some of the specific research projects underway at the centre?

There’s a whole range of different projects, but beyond the projects there is something extremely important, which is the issue of mandating indoor air quality standards. The point is that until this is done – until we have performance standards – not much will be happening.

We have such a huge body of science, we have so much technology, but it is not used beyond demonstration projects, and there’s been lots of projects. So really, it’s time for regulations on indoor air quality. This is one of THRIVE’s top focus areas.

In terms of specific projects, there’s a whole range of them.

One is economic assessment of the impact of indoor air pollution. There are not many studies like this around the world, and it’s very difficult to do. One reason is that we don’t have data about indoor environments. This work has to be done based on many different assumptions.

But we need at least a model of such an assessment, and we need to come up with specific values now and an economic cost-benefit analysis. How much will it cost to improve buildings – whether new or retrofits – compared with the cost of health effects, lost productivity, absenteeism, and so on?

This is probably one of the most complex projects, because it requires economic expertise. To me, economics is much more difficult than nuclear science! To get an economic assessment of something and to get economists to agree on something, that’s very difficult.

But we are starting this process and we will be working on this with many colleagues from outside THRIVE.

Do you think the economic study is a pre-requisite for mandating indoor air quality standards? Do we need an economic argument in place to drive it forwards at the political level?

I would like to say that it is not, because we have general knowledge. But on the other hand, hearing politicians speaking, this always comes as an important question.

If you look at the recommendations from last year’s parliamentary inquiry into long COVID, where this topic was covered, the steps they mentioned led to proposing indoor air quality standards for Australia, but the cost-benefit analysis was included.

So from whichever angle you look at it at the political level, this is important. That’s why we want to have it.

There was a study published recently in The Lancet on the burden of disease due to indoor air quality in China, and this included an economic analysis as well. This was conducted only for one type of building, which is residential buildings, and the cost came as almost 3.5 per cent of Chinese GDP. This is really huge.

But the study took more than five years to conduct. And this is only one sector. From the point of view of setting indoor air quality standards for public buildings, we’ll start working on this, and five years from now, if things go well, we’ll have this for several key sectors. But five years from now the train will have moved. So we have to do it in steps, based on anything that is available, while working on something that is much more detailed, something that could be updated with the new information, with better knowledge. There’s a short-term and a long-term plan.

Related to this is the burden of disease, which is a separate project. There would be some sharing of data between this and the economic analysis, but there is basically no burden of disease assessment for Australia for indoor air, apart from one specific aspect: mould. This is very important in the Australian context because of humidity and the climate, but it is only one angle.

One of the projects one of our PhDs will be working on is burden of disease. The idea is that we will cover at least two sectors of public buildings in addition to residential, because residential allows us to compare to other countries. Most assessments that have been done now have been done for residential sectors.

The PhD project goes for three years, but there’s only so much we can do to generate this information quickly.

What other topics will the researchers be investigating?

There’s a whole list of other projects that are similar, looking at ventilation for example. One specific aspect of ventilation that we have already started working on is displacement ventilation.

Displacement ventilation for climates across most of Australia appears to be a very good type of ventilation for several reasons.

First of all, it doesn’t mix the air, which means it doesn’t mix the pathogens we emit. So this has a very high likelihood of reducing infection transmission. It also has the potential to reduce energy use, because in principle you don’t need to deliver that much air.

But there are some complexities. One is that it is really good for cooling, because you deliver cool air at the bottom of the building, but it doesn’t work that well for heating.

Also, it relies on establishing thermal layers, which can be affected by all kinds of things. Let’s say that there’s a wall that at a particular time of day is exposed to strong sunlight radiation – things like this will affect the thermal layers.

This requires more work, but if it’s designed properly, it potentially has big benefits.

One other project that wasn’t originally included in our proposal but that is important is looking at microplastics in the indoor environment.

There’s been a lot of work about plastics in general in the outdoors and the impact on ecosystems. We’re going from very large plastics, like the plastics you see littering beaches, to smaller plastics that result from degradation of the bigger plastics. There’s been measurements of microplastics in many places, but this is mainly outdoors.

There’s been very little work done on indoor microplastics, and there’s an important science coming into this, because when we are talking about microplastics and plastics that come from the process of degradation, normally mechanical degradation only goes to a certain size. After this, if the size is a few tenths of a micrometre, the forces are not strong enough to degrade them further.

So the question is whether we have microplastics in the air only going down to these sizes, or whether there are other processes that result in the formation of smaller microplastics. In that case, what’s the situation with microplastics in indoor environments?

The THRIVE project recently opened a new lab. What kind of cutting-edge equipment do you have, and how will it support the work?

Our experimental work – because we also do modelling and assessment – consists of two aspects: laboratory studies and real-world studies. We conduct a lot of work in real environments, because ultimately, to prove or disprove something is really happening in the world, you need to work in actual buildings.

But there are some elements that can only be worked on in a lab.

The lab we have now is amazing. It’s much bigger than our previous lab, so there’s space for everything, and we have devices that we didn’t have before.

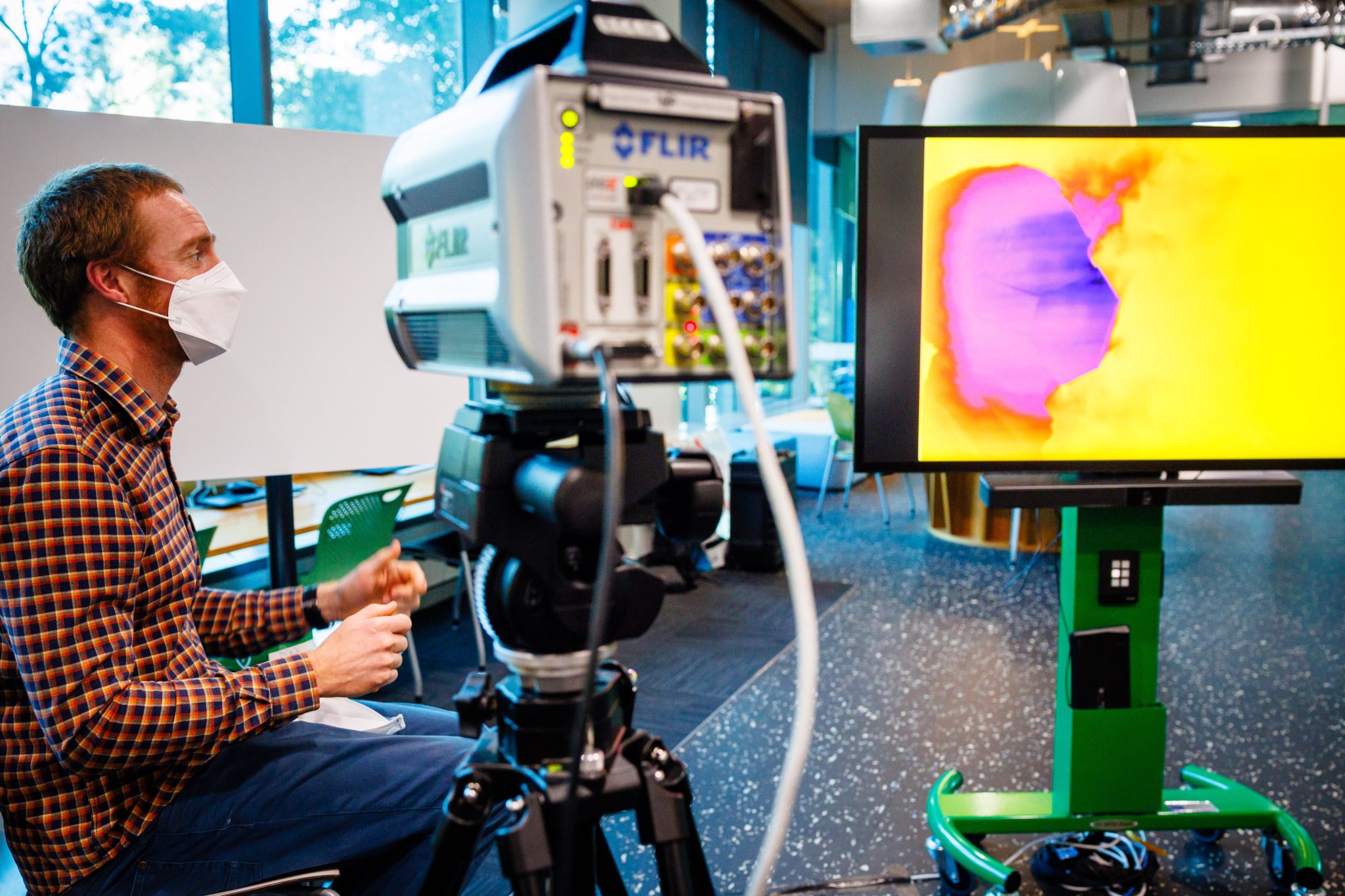

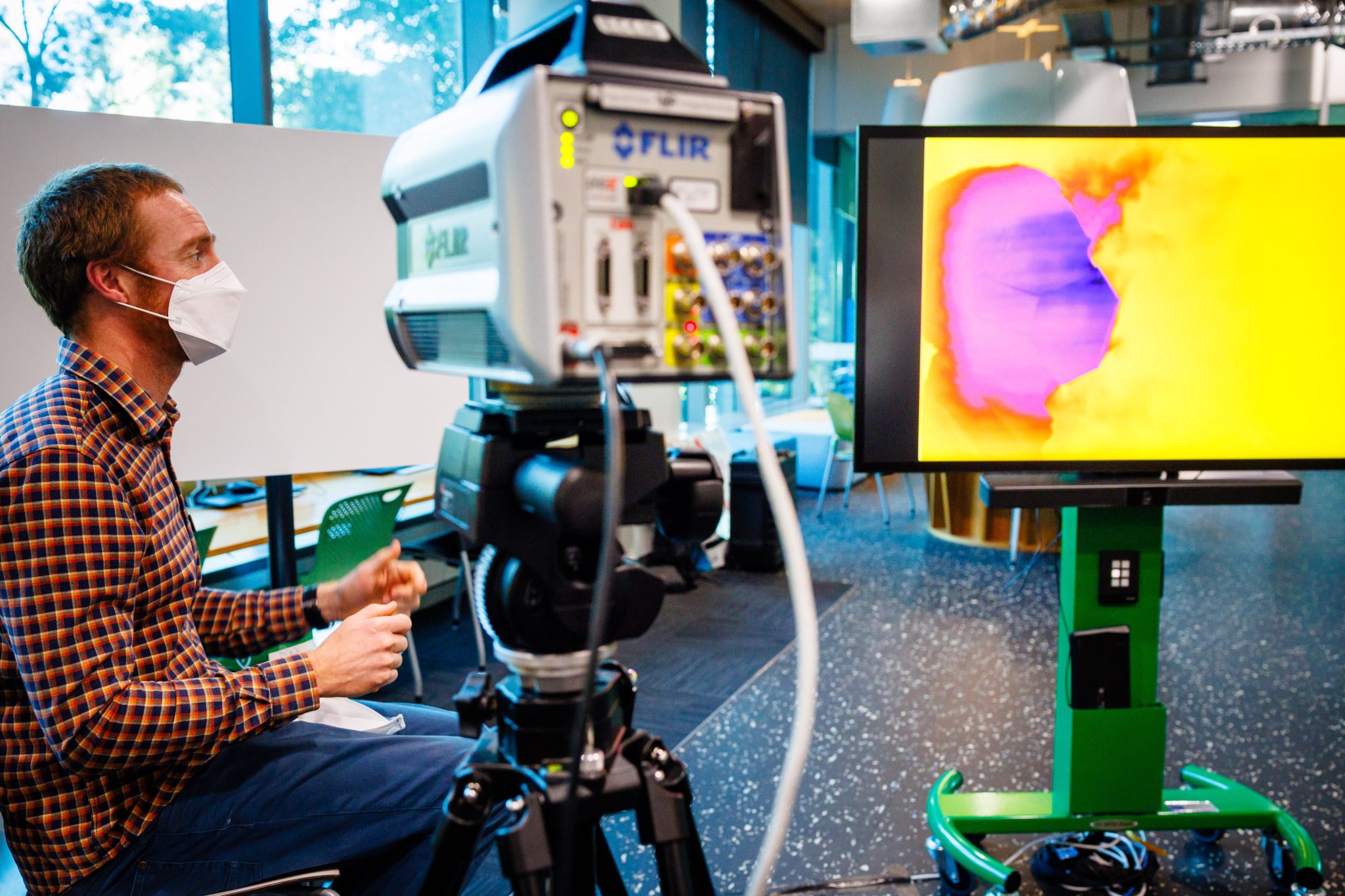

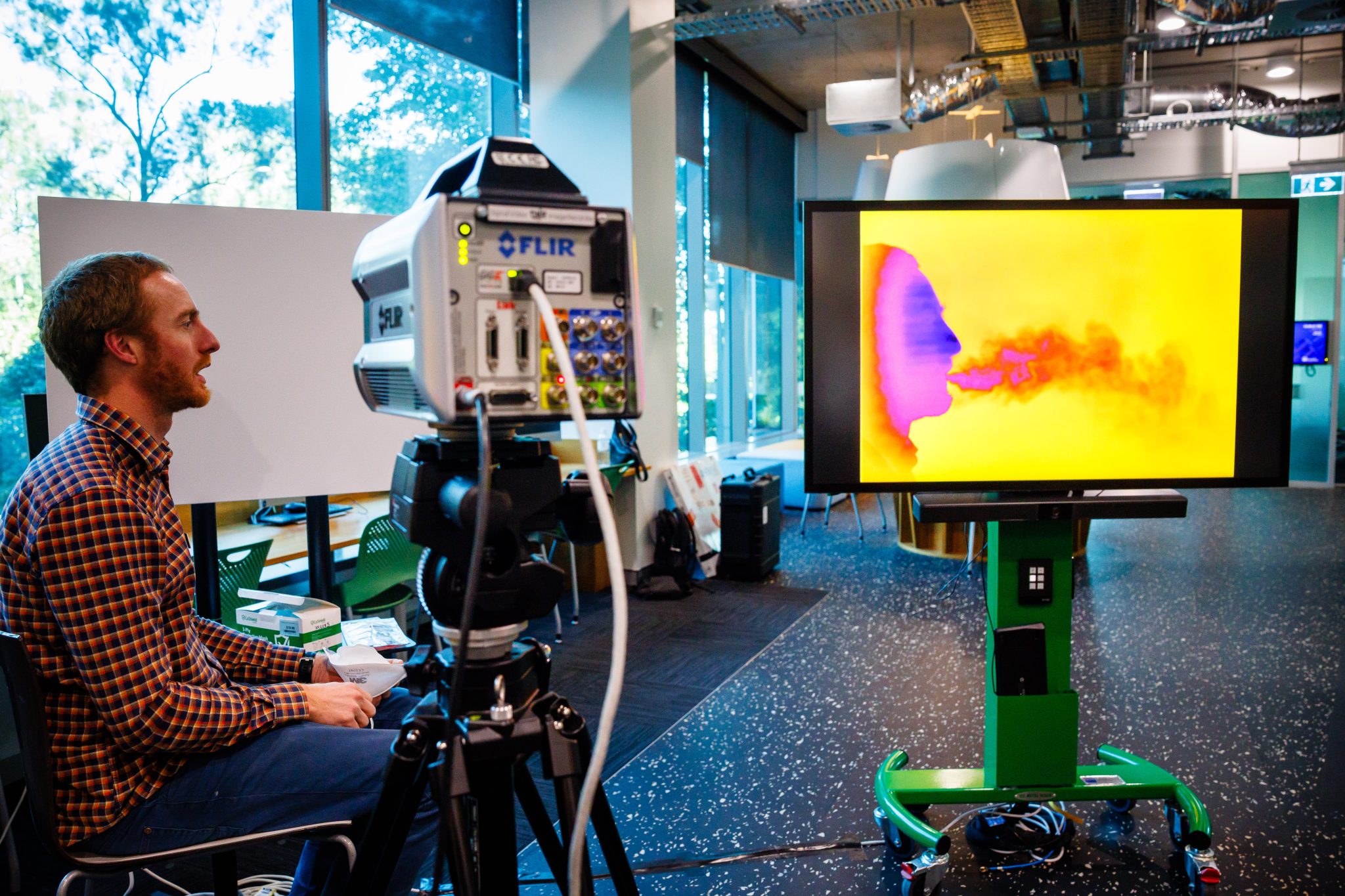

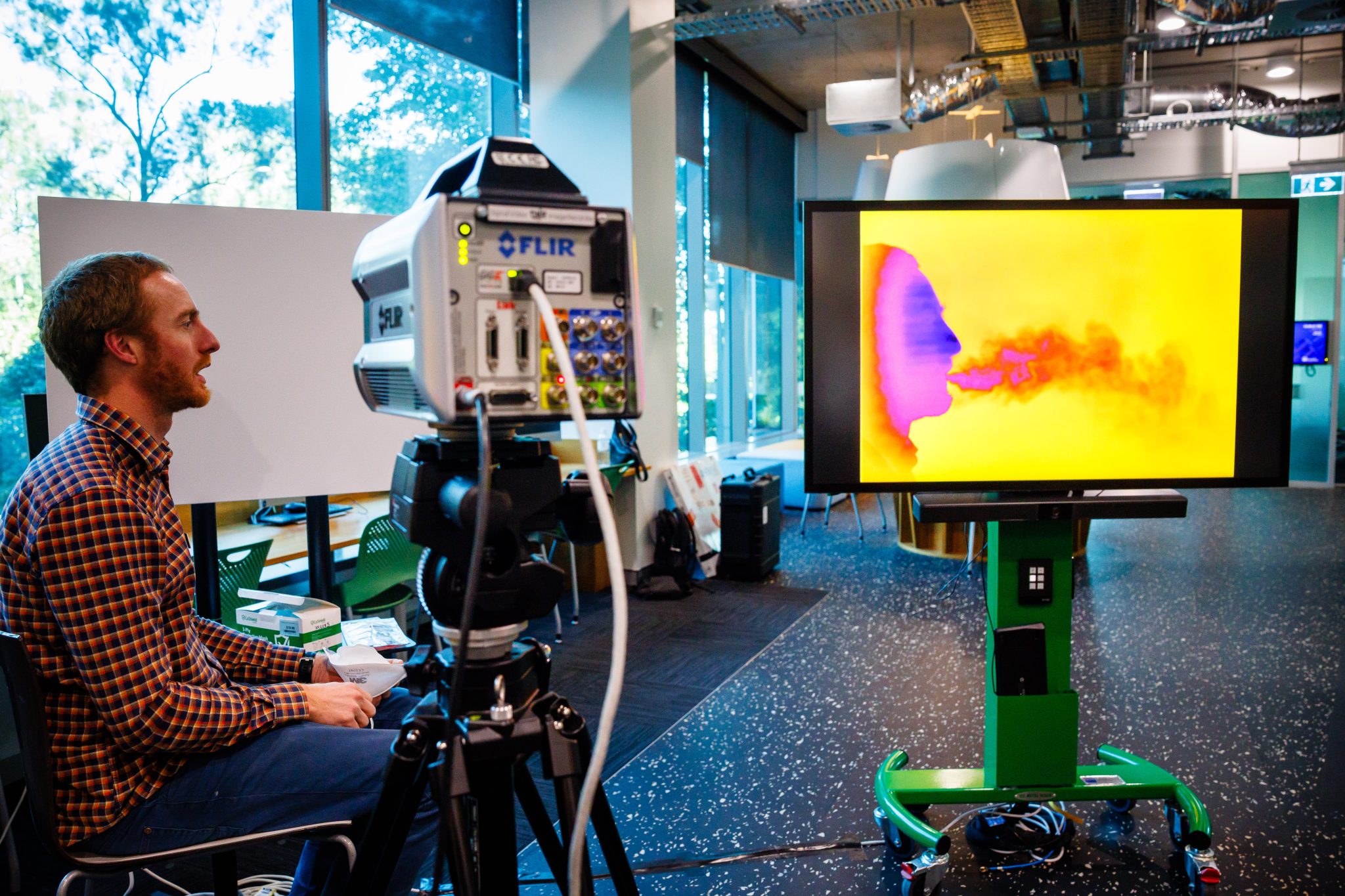

One of the systems we designed before, when we started working on particles from human respiratory activities, was a flow tunnel where we were able to study individual particles from human respiratory activities.

When we built the tunnel, it served us very well for conducting what are considered fundamental studies in this field. Then the tunnel was in one of the hospitals, where lots of experiments were done on people with cystic fibrosis.

Now it is refurbished and back in the lab, because we have space for it. And it will allow more detailed and more refined analysis – things we hadn’t done before.

First we studied the physics of the particles: concentration, size, distribution and evaporation.

When they used the tunnel to study cystic fibrosis volunteers, then it was bacteria particles. But they haven’t so far had a chance to work with particles containing viruses. This is one big toy we have.

Another one is called CELEBS. It was built in Bristol and was designed for the purposes of levitating individual particles from human respiration activities to observe what happens under different compositions to the stability of the virus in the particles.

Then we have a whole room with different mass spectrometers, and a room for studying secondary chemistry – such as what is generated from products used in buildings.

AIRAH is an industry partner in the THRIVE project. How can professionals working in HVAC&R support the work?

One area of support is data on buildings. Ultimately, this is the most important thing – that we understand what’s happening in actual buildings. If we have data across different types of buildings, this is something on which we can do assessment analysis and propose different solutions.

For example, right now we are doing a survey about displacement ventilation. For example, is it used in Australia? Or if it’s not used, what are the barriers? There are lots of questions like this where we could organise surveys.

There could be lots of surveys like this, and that’s something that I see could be very important. If we understand what’s happening in actual buildings and we have data across different types of buildings, this is something based on which we can do assessment analysis and propose different solutions.

This article appears in Ecolibrium’s Spring 2024 edition

View the archive of previous editions

Latest edition

See everything from the latest edition of Ecolibrium, AIRAH’s official journal.