How to make money from batteries

Craig Roussac from Buildings Alive looks at what investing in batteries can mean for building owners in Australia.

Saving energy saves money and reduces greenhouse gas emissions. This fact has underpinned efficiency programs and driven investment returns for sophisticated buildings owners over many years.

But the times are a changin’. We now talk about “decarbonisation,” “electrification,” and energy “optimisation.” These aren’t just fancier words – behind each is a complex web of interactions and choices that, if managed well, can supercharge profits. If managed poorly, however, they lead to material losses and perverse environmental outcomes.

In most large complex buildings, the “low-hanging fruit” has been picked. Building owners therefore have a choice: continue as they are and accept diminishing economic and environmental returns; or adopt a holistic approach to energy management that leverages data, science and technology to fully harness the opportunities from renewable energy.

Building owners are missing out

Unfortunately, most building owners are not profiting from the clean energy transition. They are missing out on the market signals that are driving massive growth in utility-scale battery storage and they are failing to capitalise on the numerous advantages they have over these commercial energy market players: e.g., proximity to demand, lower infrastructure costs, embedded controls, and operating synergies.

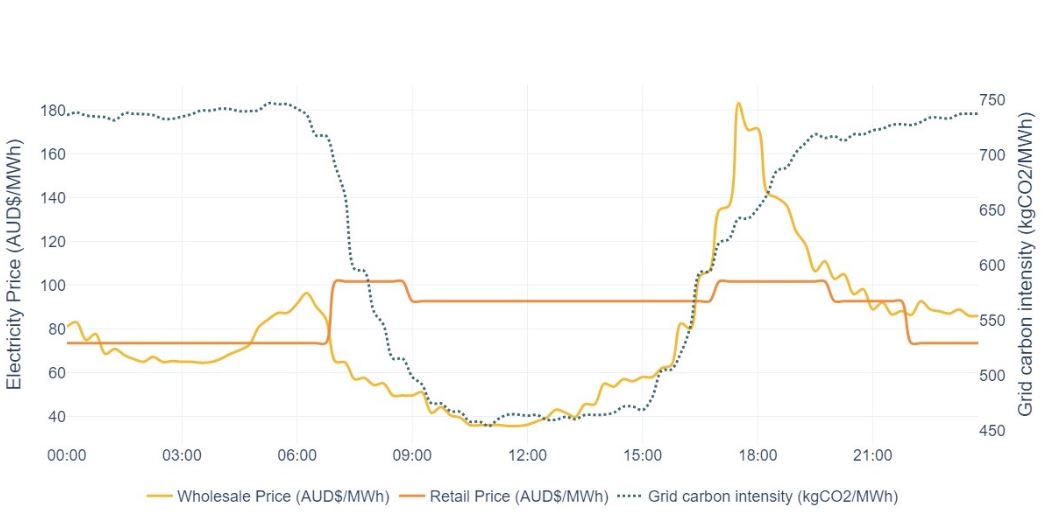

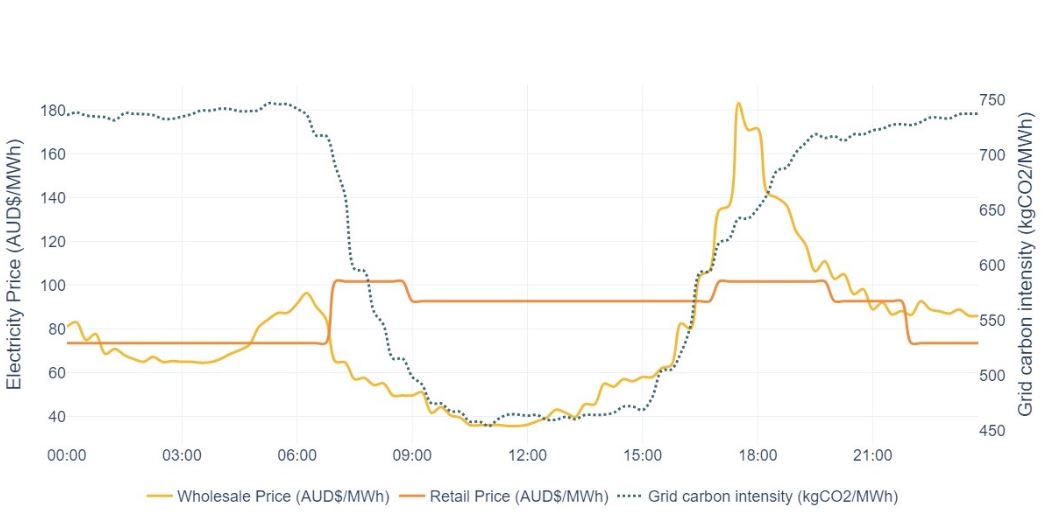

A major factor is the way they interact with energy markets. The chart below shows the average wholesale price of electricity in NSW each day from September 1 to November 30, 2023, and the electricity tariffs paid by the owner of a typical large commercial office building in Sydney’s CBD. Both lines show the tariffs paid for electricity consumption only: they exclude all network, distribution, demand, metering, etc. charges.

By purchasing fixed price electricity from a retailer, the building owner pays a higher rate on average ($87.36/MWh versus $76.33/MWh), and even more on a weighted basis since commercial buildings use more energy during the day than at night (this varies from building to building). The retailer, in its defence, requires a sizeable margin to hedge for demand and wholesale price uncertainly, and to make a profit.

Wholesale electricity prices drop in the middle of the day due to the generation of solar power – both from the amount being supplied into the grid and the reduction in demand from buildings with photovoltaics on their rooves. This is reflected in the GHG emissions intensity of the grid, as illustrated below. In effect, the building owner is not only disadvantaged by the margin being charged for electricity during the daytime by its retailer, but is also being subsidised by the retailer for its use of high-emissions intensity power at the early-morning and early-evening peaks.

What does this mean for investment?

Let’s say the owner wants to invest in a battery with the following specifications:

- 1MWh power capacity

- C-rate of 0.5 (i.e. ability to fully charge/discharge in two hours)

- Round-trip efficiency of 0.84 (i.e. 16 per cycle losses per cycle – this is considered good)

- Installed cost $340,000 ($300/kWh plus $40k installation and incidentals).

The building owner has three options for controlling the battery. They can optimise for the retail price, i.e. try to minimise the total cost of electricity under their existing retail power purchase agreement (PPA). They can optimise for wholesale price, i.e. elect to purchase directly from the wholesale market rather than have their retailer apply hedges to fix the contract tariffs. Or they can ignore price completely and just use the battery to minimise GHG emissions from their operations by using more energy from the grid when it’s cleanest. Please note that all three scenarios are fixed “set and forget” schedules – Buildings Alive supports more fine-grained approaches that can improve results considerably.

Only under the wholesale price optimisation scenario does the battery present a viable investment opportunity. If operated under a conventional energy tariff arrangement, not only would the IRR be negative and the payback well exceed the life of the battery, but greenhouse gas emissions would increase!

The good news is battery prices are falling rapidly. The better news is that batteries are but one component of a “buildings as batteries” strategy, with HVAC controls and TES both offering much better ROIs. If batteries drop in price by 30 per cent (highly likely over the coming 12–18 months), the payback on the wholesale price optimisation strategy improves to 7.2 years and IRR moves to 12.1 per cent. In other Australian states and territories, the ROI is already around these levels.

For building owners who are committed to electrification, decarbonisation and fixed electricity tariff models, the bad news is that batteries would have to fall in price by about 90 per cent to achieve a positive IRR – not impossible, but by then the opportunity to profit from a leading role in the clean energy transition will have come and gone.

About the author

Dr Craig Roussac is the CEO of Buildings Alive, having co-founded the non-profit organisation in 2012. He has a PhD from the University of Sydney, where his dissertation in architectural studies focused on energy efficiency feedback to building operators.

Craig is widely recognised for his contribution to the field of environmental performance management in buildings, particularly in relation to energy use.

This article appears in Ecolibrium’s Autumn 2025 edition

View the archive of previous editions

Latest edition

See everything from the latest edition of Ecolibrium, AIRAH’s official journal.