Commission possible

William Lane, F.AIRAH, makes the case for how formal accreditation could improve commissioning practices across Australia’s HVAC and building services sectors.

In the HVAC sector, it’s important that we don’t just think about air conditioning and ventilation systems in isolation, but instead take a holistic approach towards building wellness. This means considering factors like indoor air quality (IAQ), energy savings, and any other adjustments that can affect the working environment of the occupant in relation to overall building wellness.

With this in mind, I’m glad that AIRAH now has Special Technical Groups in fields such as IAQ, electrification, building physics, and of course commissioning. I’m also glad to see organisations such as the Testing and Commissioning Association (TACA) doing good work in this area. But I feel that the next step for improving HVAC commissioning in Australia is the establishment of formal – and mandatory – accreditation for multi-skilled commissioning technicians who oversee projects from start to finish.

What is commissioning?

Let’s start by defining a term that I believe to be widely misunderstood within the industry: commissioning.

The U.S. Department of Energy defines HVAC commissioning as “the process of thoroughly verifying and proving that building systems are installed and operating according to the criteria in the original design and engineering documentation.”

The practical aim of HVAC commissioning is maintaining a suitable indoor comfort zone while minimising operating costs. Many people consider comfort to be largely subjective and influenced by bodily sensations, temperature, thermal radiation, sound, lighting, and smells. However, there are established industry guidelines for temperature, humidity and air velocities, which are generally applied during the commissioning process. For HVAC systems, the golden zone is 21–24°C at 40–60% relative humidity.

In practice, even the most sophisticated control system cannot always achieve an ideal comfort zone. But while “ideal” and “always” are impossible goals, there are certain things within our control.

Designing a system well will improve outcomes. Commissioning it well will improve outcomes further. And tuning it will make even greater improvements. But miss one step or use unqualified people and it can all fall apart.

The role of the commissioning expert is to help optimise the system in accordance with the design intent of the overall building. As such, the end result is largely dependent on the commissioning technician’s level of expertise.

Commissioning should only be performed by a competent technician. However, at present there is no legal requirement for any specialist training in commissioning, and no mandatory accreditation process.

We’ll take a look at how formal accreditation might work later on in the article. But first let’s look at some of the problems that need to be addressed.

Problems galore

Over the years, I have been trying to raise awareness of the importance of the commissioning process associated with the installation of HVAC systems. In doing so, I have encountered a great deal of resistance.

I believe a major source of this resistance comes from a general lack of understanding of the commissioning process, or at least the failure to acknowledge its importance and the value it offers. Another major factor is that contractors often don’t budget or free up finances for HVAC systems until the end of construction projects, instead prioritising what they consider to be more important or pressing needs. This means HVAC is often “tacked on” at the end of the build, an approach that inevitably creates problems and leads to systems that are not properly designed or adjusted for how they will be used.

Think of it like this: you’ve just bought an expensive new sports car with an engine that contains only top-of-the-line, high-performance parts. However, once you take the car home, you realise that none of those parts have been properly tuned to achieve their performance capabilities. You then discover that tuning them would cost you a lot of time and money on top of the huge sum you’ve already paid for the car. You’d be furious, wouldn’t you?

A building is much the same. It’s imperative that the correct timeframe and funding are made available at the beginning of the project – and that this is professionally managed – to ensure that the end product is what the client actually ordered. This can be challenging when the contractor is running short on funds towards the end of a project, especially if they’re trying to cut costs for the sake of profitability.

As it stands

At present, there are several independent commissioning companies that fill a significant void within the industry. Instead of training their own technicians in commissioning, many companies outsource this responsibility to one of those independent companies.

At best, they do this to access expert services as and when needed. At worst, it’s simply an exercise in cutting costs.

The problem is that you don’t always get the level of skill, knowledge and accountability you’re looking for when you outsource. Let’s look at an example of the impact a commissioning technician can have on a facility.

When measuring airflow, we develop factors to correct the reading of the instrumentation used. There are processes to calculate this value, and if they’re not applied correctly, it can significantly impact the effectiveness and efficiency of the system.

An untrained commissioning consultant might apply a factor of 1.1 to a toilet exhaust grille when they should have used a factor of 0.8. In this example, the factors look similar enough, but the result is a 37.50 per cent difference in airflow rate, which can mean a huge difference in performance. This mistake can cause discomfort, increase energy consumption, and can even create other issues as it compounds, including rushing noises from the additional airflow.

In some cases, consultants insist that an independent balancing company with no affiliation to the manufacturer or mechanical contractor must be used to remove any doubt about the accuracy of their readings. Situations like this can quickly add to the complexity and cost of a project.

As technology changes, so must we review our methodologies and working practices. We need expert commissioning personnel to accept responsibility for the works performed and sign off on those that have been performed correctly. It’s time to take responsibility and show that we are serious about our credibility by signing our work off directly.

The answer: accredited commissioning technicians

I believe the industry needs to formally train and accredit commissioning technicians to understand the original design intent of HVAC systems as laid out by the design engineer. Training, licensing and registering commissioning technicians is the best way to avoid the problems we’ve discussed above.

These commissioning technicians would be multi-skilled and accredited in a diverse range of relevant fields. Below is a summary of their objectives and responsibilities:

Objectives:

- Confirm that the design intent has been achieved

- Achieve a predictable return on investment (ROI) for the owner

- Ensure that each individual item of equipment – whether automated or not – operates as required

- Confirm that each individual item of equipment is correctly integrated into the building management system.

Responsibilities:

- Test and verify the performance of equipment against the design criteria

- Adjust and calibrate equipment to achieve the design intent

- Ensure that the system is working in the manner for which it was designed

- Record all readings for future reference.

Components of accreditation

The commissioning technician should be suitably skilled, with a level of accreditation that matches their skillset and experience. I propose that accreditation in commissioning should involve the 13 areas of expertise outlined below:

1) Refrigeration: Components, lubricants, refrigerant types, refrigerant transfer, leak testing, recovery & recycling, evacuation, charging, welding, electrical & controls, defrost timers.

2) Controls: Electrical – wiring diagrams & schematics, electronic, pneumatic, measuring devices used, electromagnetism & inductance.

3) Electrical: Ohm’s law, inductance & capacitors in HVAC systems, overload protection devices, transformers, motor start & variable speed controllers, wiring diagrams & schematics.

4) Plumbing: The installation of HVAC components, welding, gas, water, steam.

5) Air balancing: Methodology used (ratio, proportional), variable speed controllers, understanding HVAC components.

6) Water balancing: Methodology used (ratio, proportional), variable speed controllers, understanding HVAC components.

7) Psychrometrics: Understanding psychrometrics – properties of air, effects of humidity.

8) System components: Understanding all system components that are used in HVAC systems, where & why they should be used.

9) Steam: Properties of steam, safety when using steam.

10) Worksite & personal safety: Understanding the components that you are working with and the risks to personal safety.

11) Customer communication: Liaison with the customer, communicating clearly and respectfully, managing budgeting and customer expectations.

12) Documentation of results: Ensuring that results are true & accurate.

13) Test instrumentation: Understanding the accuracy of the test instrumentation, when & where to use.

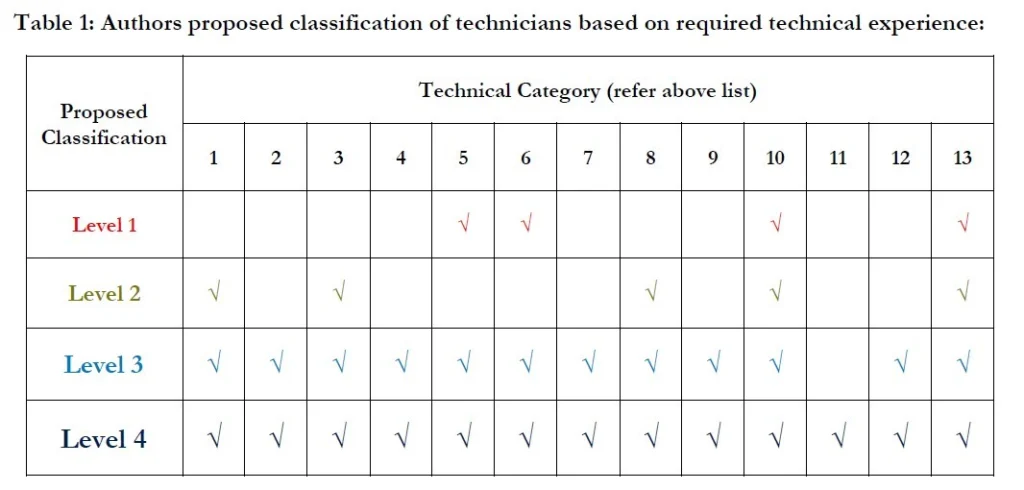

The levels of accreditation would consist of various combinations of these units of competency. I propose four levels of accreditation for commissioning technicians. This would provide easily recognised and uniform standards for the industry, thus improving the overall quality of HVAC commissioning in Australia:

- Level 1: Basic entry (items 5, 6, 10 & 13)

- Level 2: Service technician (items 1, 3, 5, 6, 8, 10 & 13)

- Level 3: Senior technician level 1 (1–10, 12 & 13)

- Level 4: Senior technician level 2 (1–13)

Continuing improvement

To achieve these goals, all those working in the industry should undertake additional training and certification. I believe we need mandatory ongoing education for each level of accreditation to ensure that technicians keep up to date with the latest industry innovations. For example, this might involve 12 hours of continuing professional development (CPD) activities over a two-year period.

Implementing a CPD requirement would ensure that technicians’ knowledge continually develops. This would also create a clearer and more stable career path for commissioning professionals.

I have long argued that establishing this career path for commissioning technicians is necessary. These professionals are often forgotten about in between projects, but having someone with the skills and experience to see a project to completion and ensure that HVAC systems are performing as designed should be a top priority for all employers in the industry.

AIRAH has shown that it is serious about the importance of HVAC commissioning. Now I’d like to see the Institute go one step further and push for formalised accreditation in this sector.

About the author

William Lane, F.AIRAH, began his career as a plumber before moving into HVAC&R, eventually running his own company as a commissioning technician. He has been an active member of AIRAH since 1987, achieved fellow membership status, and was honoured in AIRAH’s 100 Faces project in 2020, having also received a Master Plumbers award in 2010. One of William’s greatest honours is coordinating the AIRAH Legends group, where long-serving members gather to socialise and share knowledge.

This article appears in Ecolibrium’s Winter 2025 edition

View the archive of previous editions

Latest edition

See everything from the latest edition of Ecolibrium, AIRAH’s official journal.