HVAC in the outback

A program in South Australia’s APY Lands is retrofitting housing to study how homes can withstand one of the world’s harshest climates.

For those of us living in major cities, it’s easy to forget just how big – and climatically diverse – Australia is. From the steamy northern tropics to the snow-capped mountains of Tasmania, each region of our vast country presents its own unique set of challenges for HVAC and occupant health and comfort.

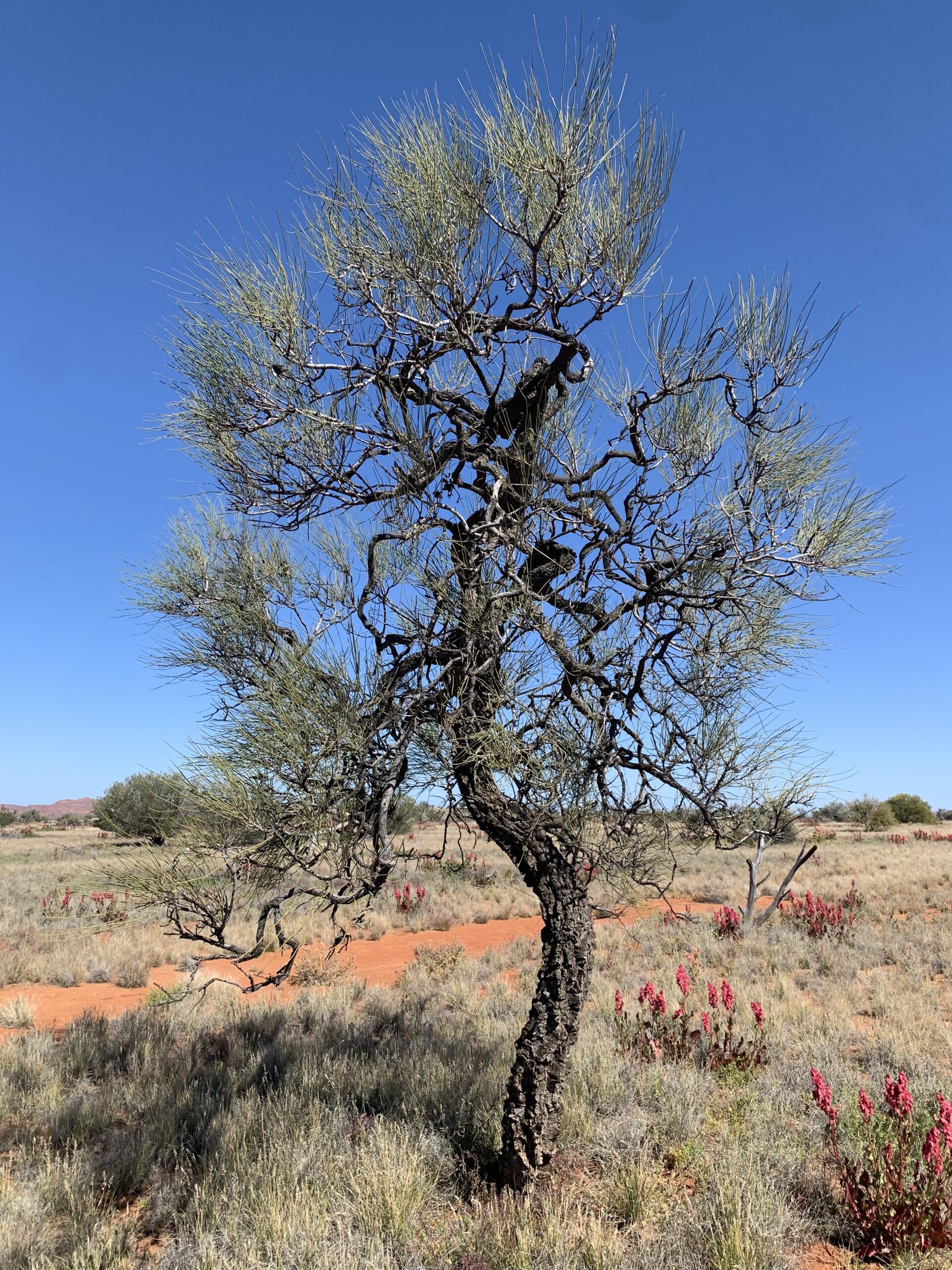

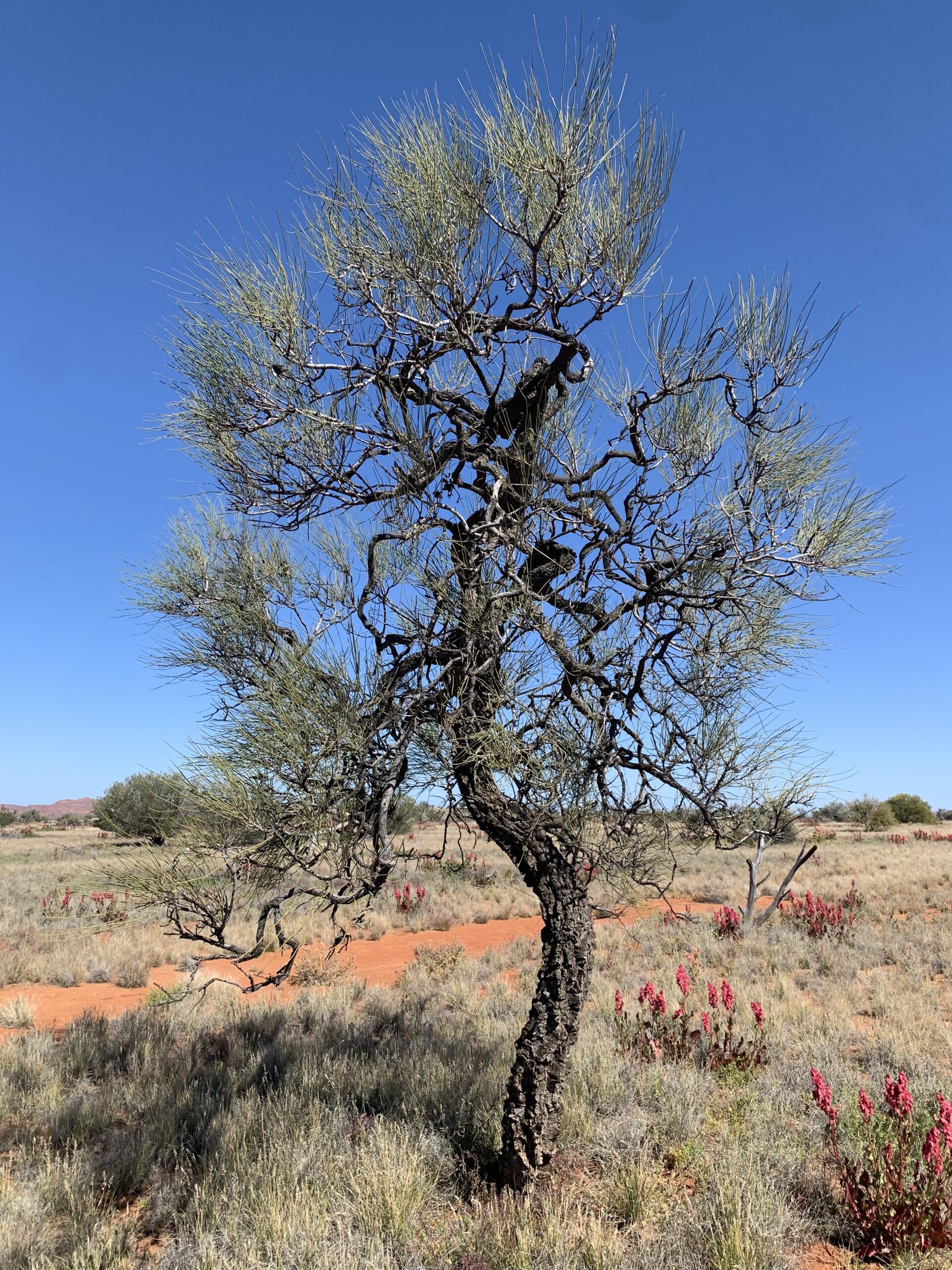

Of all these climatic zones, none come harsher than the red centre. Here, daytime temperatures during summertime regularly threaten 50°C, while the mercury plummets below zero during those freezing winter nights.

Couple these temperature extremes with an almost unfathomable degree of physical isolation from major cities and you get the Aṉangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) Lands – a stunningly beautiful region of the country that very few Australians will ever set foot on.

One of the biggest challenges in isolated regions like the APY Lands is building affordable housing that is durable enough to withstand the rigours of the outback, but that can also provide thermal comfort when hot and cold extremes occur, often on the same day.

Now, an ambitious project is investigating smart retrofits for housing in this challenging environment.

Home improvement

The APY Lands Energy Efficiency Retrofit Pilot, part of the national RACE for 2030 Cooperative Research Centre, is a collaborative effort led by the South Australian government, the University of South Australia (UniSA), and a number of industry partners.

Since launching the pilot in December 2023, the project team has installed energy monitoring devices in 12 households and completed retrofits on six homes in an APY community. The homes are managed by the SA Housing Trust.

The trial retrofits are targeted solutions to reduce air leakage, increase insulation, and reduce thermal bridging – where heat or cold bypasses insulation through the steel building frames.

With 15 project and industry partners, the team has assessed 20 homes, interviewed residents, installed monitoring equipment, built two test rooms in Adelaide, and modelled over 100 retrofit scenarios.

Lead investigator, UniSA Sustainable Engineering Systems researcher Professor Ke Xing, says the project combines scientific rigour with practical on-the-ground training.

“This pilot is not only improving living conditions in one of the toughest climates in Australia; it’s also providing practical options for future upgrades in remote and regional communities across the country,” Xing says.

“In the past year we have collaborated closely with the community, local maintenance workers and our industry partners, all of whom have shown an extraordinary commitment.”

Professor Ke Xing

From an HVAC and building physics perspective, it’s a project unlike any other.

Welcome to the APY Lands

The Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) Lands are a culturally rich but sparsely populated region in the northwestern corner of South Australia.

The region makes up more than one-tenth of the state’s geographical area, but only 0.13% of its population. That’s just over 2,300 people living in 103,000km2 of land. To put that in perspective, South Korea is slightly smaller in terms of area – 100,000 km2 – but has a population of 52 million people.

Local resident Renee Singer says that, while it can be difficult being so isolated, living close to family, breathing fresh air, and enjoying the peace and quiet of life on Country is irreplaceable.

“It is not an easy life, but it is a simple life,” Singer says. “You can take your family out to nature. There’s not much traffic in the community, so it’s good for kids to be out and not worry about them.”

For Sean Maxwell, AM.AIRAH, who is involved in the housing retrofit project in the APY Lands, the cultural heritage and physical beauty of the region made an instant impression.

“I was first struck by the austere beauty of the land and the richness of colours,” Maxwell says. “I was told that a few good years of rain had made for unusually vibrant flowers, but I hope it is like that every time I visit – stunningly beautiful.”

Converging challenges

Sean Maxwell, AM.AIRAH, is Scheme Manager for the Australian chapter of the Air Tightness Testing & Measurement Association (ATTMA). He is also the chair of AIRAH’s Building Physics Special Technical Group (STG).

Maxwell was engaged as an HVAC and building physics expert on the housing retrofit project. He initially travelled to the APY Lands to test the air tightness of houses, but quickly discovered that there was much more that needed to be done.

“My involvement in the project was first limited to a request for testing homes for airtightness, but it quickly became clear that the range of performance problems was far broader and deeper. My expectations were swiftly set aside as I viewed the many interlinked social, geographic, and economic dimensions of the challenges.”

As Maxwell would discover, HVAC in the outback presents an array of barriers to create a challenging but extremely rewarding project.

An unforgiving environment

It’s not just the extreme temperatures that make the outback difficult for HVAC work. Maxwell points out a range of environmental issues that add to the complexity of providing thermally comfortable housing.

“There’s an outback factor I was told to take into consideration; everything you think you know about Melbourne or Sydney just doesn’t work the same out here,” Maxwell says.

“It’s a very dry environment. The horses and camels are so thirsty that they’ll come and knock over pipes to get water; there are concrete rims there to prevent them from doing that.”

That extreme dryness causes some serious flow-on effects for HVAC equipment.

“Evaporative coolers were the system of choice because it’s so dry there,” Maxwell says. “But because it’s so dry, the highly mineralised local water builds scale quickly, and that requires more maintenance.

While the obvious solution might be to replace those evaporative coolers with split system air conditioners, there are other factors that complicate this.

“They tried replacing evaporative coolers with split systems, but because of the cold, pests huddle around the warm circuit breakers,” Maxwell says. “Insects would get in and short the electronics – you need insect-proof air conditioners.”

Maxwell notes that even something as universal as insulation is far from simple in the outback.

“Dust comes in, settles on the insulation, and causes it to fall over time,” he says. “There’s also tunnelling by rodents that go through, tear it up, and make a nice fluffy home for themselves.”

These factors explain why local housing has been built to prioritise toughness over other considerations.

“The homes are necessarily built of extremely durable materials, like steel framing that is immune to termites, metal cladding that can withstand temperature extremes and low maintenance, and evaporative coolers with few moving parts,” Maxwell says. “All the wall and ceiling linings are made out of really tough stuff like solid metal and plywood.

“The built form is therefore durable but inefficient, with extremely low thermal mass, extremely high thermal conductivity and extremely high air infiltration.”

The tyranny of distance

The study found that the extreme geographical isolation of communities in the APY Lands further complicates efforts to make housing more energy efficient.

“One challenge is simply the distance, with Adelaide at least a 12-hour drive away,” Maxwell says. “Getting personnel and equipment there to do something as common as an air tightness test is neither routine nor inexpensive.”

It’s not just transport and shipping that adds to the cost of any HVAC work in the region. Maxwell also points out that skills shortages have resulted in low availability and high labour costs – often around $150 per hour for any kind of work – making even the smallest inspection or repair difficult and expensive.

In response to this, the project team has produced household energy efficiency and trade training education materials in consultation with the community and the project’s Industry Reference Group, to ensure residents know how to get the best outcomes in their homes.

Local tradespeople have been trained on-site, supported by custom training resources and guidance from retrofit experts. There was also a “train the trainer” event in Adelaide in 2024, involving the Department for Energy and Mining, the SA Housing Trust, TAFE SA, Renewal SA and staff from a building contractor. Local TAFE students were provided with Net Zero Energy Builder Scholarships to support energy efficient construction in the APY Lands.

Bolstered by these programs, local trades will take part in rolling out the retrofits to remaining APY households.

The human factor

Another challenge is helping residents understand how to best stay comfortable in their homes after the retrofits. Maxwell points out that occupants have spent years adapting to the extreme conditions, and some of those behaviours will be difficult to unlearn.

“Many houses in this region are designed to manage summer heat, but they can be extremely uncomfortable in the winter,” he says.

“Even if homes perform better when sealed up, one cannot assume they will be operated that way. The same change in mindset is true worldwide, when energy efficiency is a new thing.”

“Many houses in this region are designed to manage summer heat, but they can be extremely uncomfortable in the winter,” he says.

“Even if homes perform better when sealed up, one cannot assume they will be operated that way. The same change in mindset is true worldwide, when energy efficiency is a new thing.”

Maxwell was taken aback to discover the measures some occupants take to heat their homes when traditional approaches don’t do the job.

“Houses are fitted with combustion heaters. However, fuel is often scarce, so radiant heaters are used, and some people use their stove as a heater,” he says. “Because of this, some houses can use around 100kWh of electricity per day during winter, compared to typical on-grid housing in SA of around 25kWh per day.”

The community perspective

Renee Singer is a member of the local community. She has been working with the RACE for 2030 Energy Efficiency Retrofit Pilot team to engage local people with the project.

Singer says homes that don’t adequately protect people from the elements can have a major effect on people’s livelihoods, including their education and employment.

“If it’s hot and people don’t have power for cooling at night, then going to work can be hard the next day,” Singer says.

And while evaporative cooling helps, the local people often take a more natural approach to beating the heat.

“Sometimes they take kids out for swimming in dams if there is water in them, or make pools from cut rainwater tanks,” she says.

Winter presents potentially more difficult challenges, with the houses often harder to heat than they are to cool.

“Winter cold can be bad for health – if it’s cold in the house people can get sick, and kids can’t to go to school if they get sick,” Singer says. “In winter they go out in the sunny areas to keep warm and make fire outside. They stay inside when the day is cool and use a radiant heater.

“Some people with cars can go and collect wood for combustion heaters, but they only do it for their house – not everyone has cars. There used to be a program to get wood for community, but not anymore.”

One of the key issues here is financial. When it takes so much energy to heat and cool your house, the costs can pile up and eventually become unaffordable.

“People have to pay for all sorts of things and it’s very hard if they are on Centrelink, so sometimes they don’t have money for power,” Singer says.

Singer hopes the project will help members of the local community “know more about the houses they are living in”, and also points out that improving thermal performance is particularly important for many people with health issues.

“After the project, they will be good houses that will be warmer in winter and cooler in summer, especially for elderly people and kids,” she says. “Kids will get a good night’s sleep and those on medications won’t have to use the aircon as much..”

Renee Singer

Real-world improvements

On their first visit, the project team identified a range of common issues across the housing stock, as well as some solutions that could potentially alleviate these issues.

In 2025, the project team were able to return to the community and implement some of those solutions to reduce air leakage in the homes.

“The team has replaced leaky bathroom fans with ones that seal effectively when they’re not working,” Maxwell says. “We’ve also sealed the ceiling joints and the door frames.”

By far the biggest culprits for air leakage are the systems designed to keep people cool during summer.

“Evaporative coolers were a huge point of ingress, mostly from the units themselves,” Maxwell says. “Any time the wind blew, it would suck air right out of the house. That’s why people were cold in winter, because the evaporative coolers were open 24/7.”

The solution? Humble dampers, which stop airflow when the units aren’t operational. Continuous insulation has also been added to the walls and ceilings of the houses.

So far, the results have been impressive.

- The dampers have dramatically improved the buildings’ air tightness, lowering the average air changes per hour (ACH) from six to below one. For an inexpensive piece of kit that takes around 90 minutes to install, the value is clear.

- Adding bulk insulation to the ceiling cavity (on top of existing insulation) has proven simple and effective, dramatically reducing thermal bridging. Insulating the walls is much more labour intensive, but has also helped reduce thermal bridging meaningfully.

- Sealed bathroom air fans have proven highly effective in reducing air leakage.

- Kitchen air fans have also proven effective, although residue from cooking oil and grease causes some issues with operation.

- Sealing the gaps around window frames and doors has helped air tightness, but finding durable materials that will last for years is challenging.

- Tenants have commented on improved thermal performance after every stage of the retrofit, noting that houses require less cooling in summer and less heating in winter.

Pre-retrofit, the air tightness of houses ranged from 19–32 ACH. Post-retrofit, that number was reduced to 9–15 ACH, representing anywhere from 42–65% improvement.

Longer term, Maxwell would like to introduce a more holistic approach to building in the outback to minimise reliance on mechanical interventions.

“If there were one larger change to the built form I would like to investigate, it might be adding more massive materials such as compressed earth, which can be locally sourced,” Maxwell says. “Used properly, with continuous insulation and better airtightness, these might help buffer some of the extreme day-night swings in temperature and make the homes more comfortable and energy efficient.”

Lasting impact

Professor Xing says that, more than a year on from the pilot project’s first interventions, the retrofit measures seem to be making a positive impact.

“Common feedback from residents was that their homes were cooler this summer, due to the retrofits,” he says. “That anecdotal feedback supports our early testing, and we are in the process of conducting full evaluations over the 2025 winter.”

SA Department for Energy and Mining Project Manager Lynda Curtis has been one of the driving forces behind the retrofit project. She hopes that success in the APY Lands will pave the way for similar retrofit programs across Australia.

“First Nations people have lived in Australia’s desert regions for tens of thousands of years, but temperature extremes have become more pronounced due to climate change.

“With broader climate extremes and overall hotter summers predicted for the future, how people are living and maintaining healthy communities on Country is of growing concern, and we are invested in providing solutions to those challenges.”

“Ultimately, we want this project to inform national guidelines for remote housing upgrades, tailored to the needs and voices of First Nations communities”

Lynda Curtis

Awe and admiration

Maxwell is full of admiration for the team who have led the retrofit project.

“SA Housing and the project team have been truly amazing to work with,” Maxwell says. “It’s been an honour to work with such a committed team that really does want to make things better. There’s no way you can work on the lands for so many years if you don’t really have a passion.”

Being involved in the APY Lands retrofit project has given him a fresh perspective, not just on his work, but on his own place in the world.

“I was struck by the cultural resilience of the communities, who maintain their identity and connection to this land they have known for thousands of years,” he says..”

Sean Maxwell, AM.AIRAH

“I have moved around my whole life. If I imagine my family had remained somewhere for thousands of years, how could my soul not be tied to that very ground? This is a very powerful concept that I have to admit I hadn’t truly considered until now.”

Maxwell is honoured to have met some of the communities of the APY Lands and got a sense of their lived experience. And while he hopes his expertise in HVAC and building physics can play a small part in making the residents’ lives healthier and more comfortable, he is overwhelmed by the cultural knowledge and wisdom he has encountered there.

“When I think about it, I am a rootless nomad in comparison,” he says. “Now here I am, bringing infrared cameras and blower doors, continuous insulation and reverse-cycle air conditioning – the nomad telling these people how they should live on their own land. I have to admit it sounds quite ridiculous.”

Project team

RACE for 2030 Cooperative Research Centre

- University of South Australia (UniSA) (Project lead)

- South Australian Department for Energy and Mining (Project lead)

- SA Housing Trust (Project lead)

- Aboriginal Affairs and Reconciliation in the SA Attorney-General’s Department

- TAFE SA

- Air Tightness Testing and Measurement Association (ATTMA)

- Efficiency Matrix

- Insulation Council of Australia and New Zealand (ICANZ)

- Powertech Energy

- Kingspan

- Sika Australia

- Nganampa Health Council

- Healthabitat

- DeepSpace-CodeSafe Solution Services

- Pointsbuild

Follow the project

To learn more about the APY Lands Energy Efficiency Retrofit Pilot via the RACE for 2030 website, click here.

This article appears in Ecolibrium’s Spring 2025 edition

View the archive of previous editions

Latest edition

See everything from the latest edition of Ecolibrium, AIRAH’s official journal.