Electrifying the harbour city

Muhammad Ali, M.AIRAH, from energy consultancy Arcadis Australia Pacific explains how Sydney could soon generate 75% of its energy needs from local renewable sources. recede go here please

When our research team set out to test how much electricity metropolitan Sydney could generate on its own rooftops, the answer surprised even us: up to 75% of its energy needs. In practical terms, this means shifting from reliance on distant coal plants to a network of solar-powered homes, commercial buildings, and community batteries distributed across the city.

The results were recently published in a report titled Sydney as a Renewable Energy Zone. This article will explore some of the key discussion points to come from the report.

Reaching 75%

Generating three-quarters of its energy needs seems like a tough ask for any city, especially one as big as Sydney. But when we consider the potential of rooftop solar, we need to think beyond the city centre.

While downtown high-rise buildings have limited roof space (only about 5% of a CBD building’s power could come from solar), vast industrial estates on Sydney’s fringes could generate five to 10 times their own energy needs, producing surplus power to support nearby homes and apartments that lack solar access.

Sydney’s existing distribution grid is well equipped; it has the capacity to carry this locally generated energy to where it is needed, which would immediately boost energy independence and reliability.

In short, the ingredients for a self-reliant energy system – abundant sun, rooftops, batteries, and a capable grid – are largely present in Sydney. The challenge is knitting them together into a coherent whole.

Opportunities and innovations

There are many innovative solutions and pilot projects pointing the way forward for Sydney’s renewable transformation. Key opportunities include:

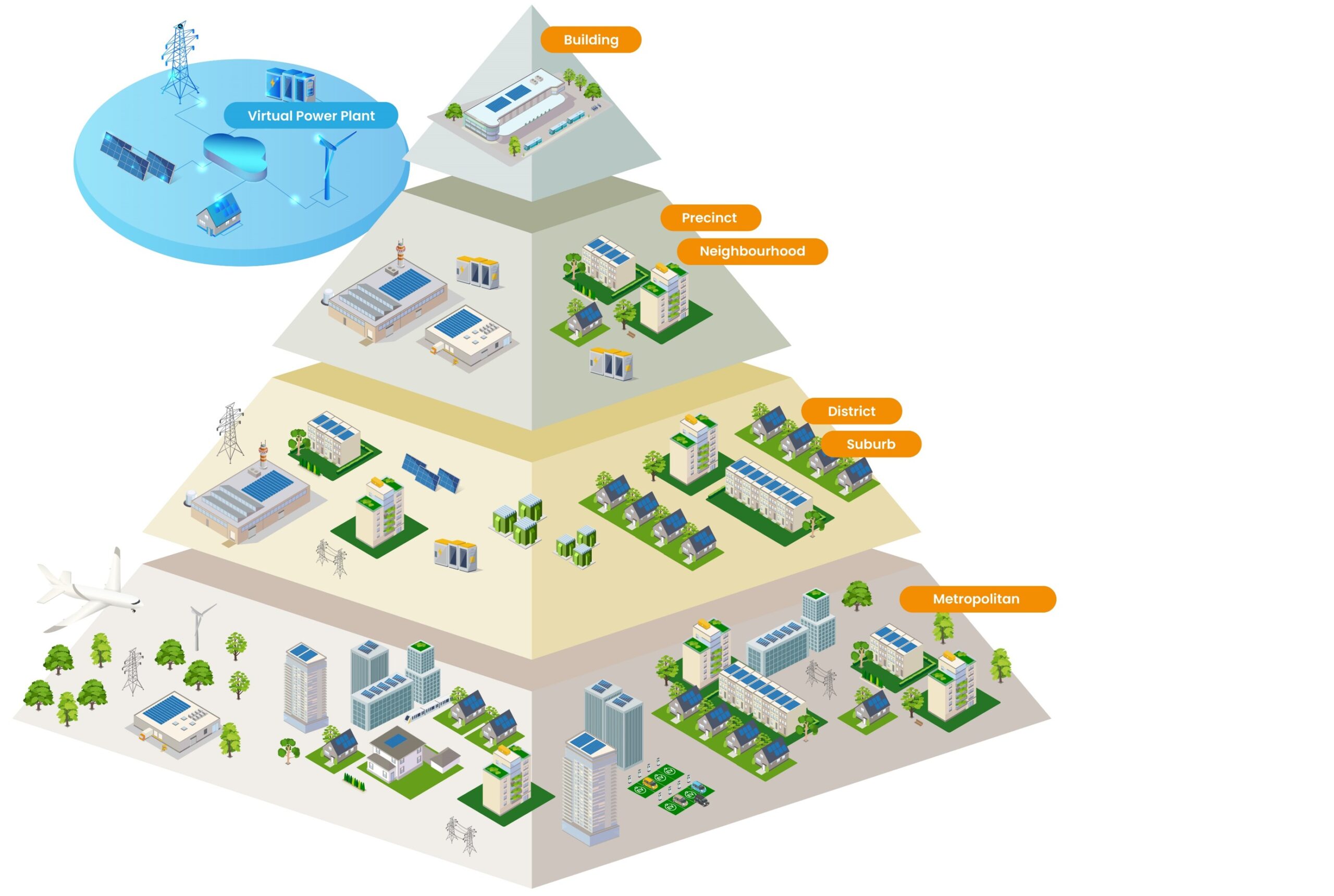

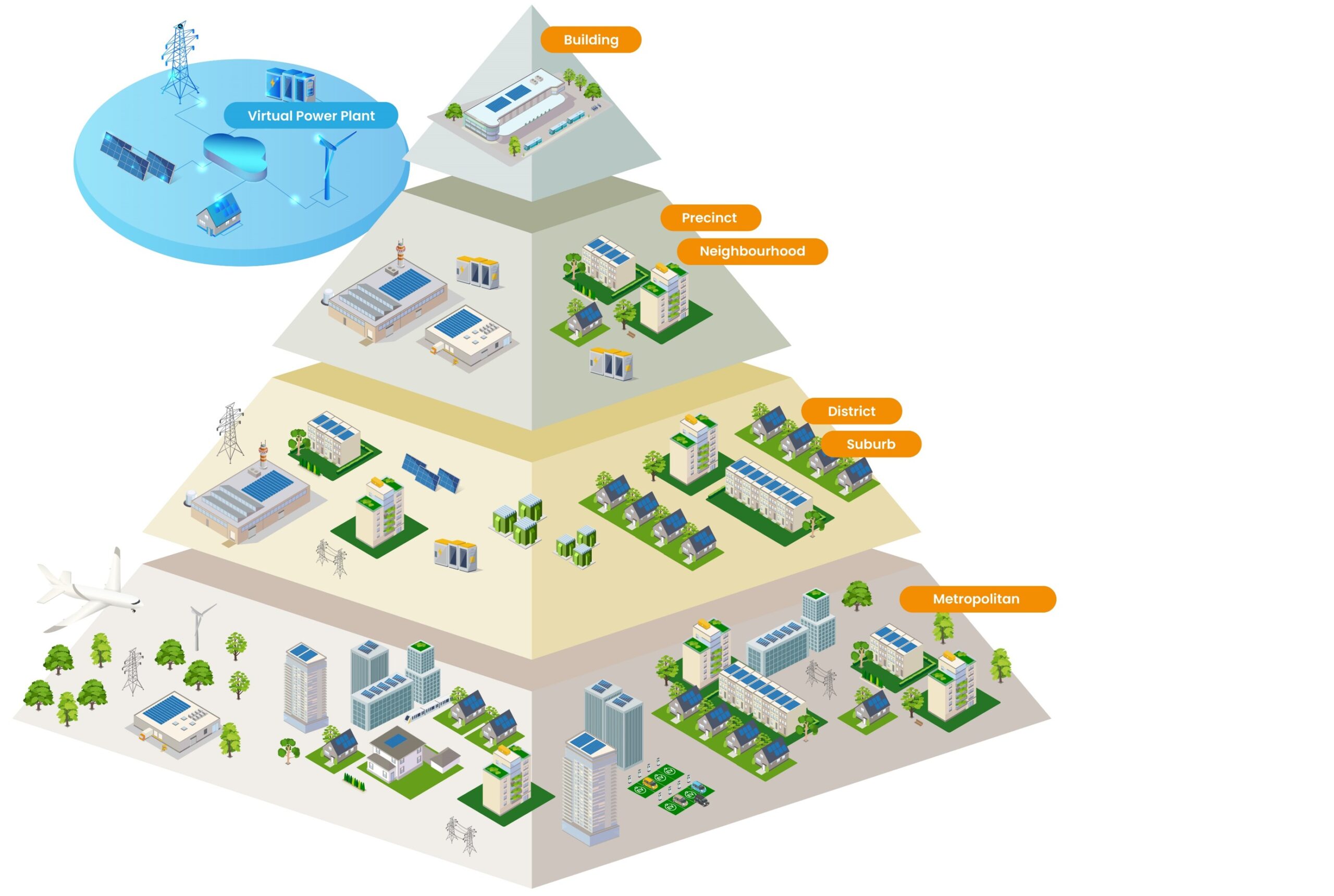

- Virtual power plants (VPPs): These are essentially digital power stations that connect hundreds or thousands of small-scale systems, including rooftop solar panels, home batteries, smart appliances, and even electric vehicles. VPPs then coordinate their output to improve their efficiency. A VPP can smooth out the variability of solar by intelligently distributing stored energy when and where it is needed, rewarding participants for supporting network stability. Our report highlights VPPs as a flexible tool that could span all scales, from individual homes to whole districts.

- Community batteries: One way to extend solar benefits to those without a sunny roof is through neighbourhood battery storage. These are medium-sized batteries installed in suburbs or apartment complexes, where multiple households can store excess solar power and draw from it after dark. Community batteries enable renters and apartment residents to partake in the solar revolution by effectively sharing storage capacity. Several councils and utilities in Sydney are exploring community battery trials to deliver cheaper, cleaner power locally and improve grid resilience at the street level.

- Industrial solar hubs: Sydney’s warehouses and industrial estates present a huge opportunity; not only can they host massive rooftop solar arrays, but they can also generate far more than those facilities alone consume. Some industrial areas could produce 500–1,000% of their own energy needs if fully outfitted with solar. That surplus can feed back into surrounding neighbourhoods, effectively turning industrial zones into clean power hubs. Capturing this potential will require new business models (for instance, landlords and tenants sharing costs and benefits) and possibly government incentives to encourage oversizing solar installations. There is also interest in co-locating large batteries at these sites to bank daytime energy for the evening peak.

- Urban renewable energy zones: Adapting the successful regional renewable energy zone concept to the city, an urban renewable energy zone (UREZ) is a coordinated local energy network that integrates rooftop solar, batteries, EV charging, and demand management across a community. Rather than individual buildings acting alone, an UREZ enables power sharing within a suburb or district, maximising the use of existing power lines and substations. South of Sydney, the Illawarra region is slated to host NSW’s first UREZ. If successful, these zones could be replicated across Sydney, creating pockets of self-reliant clean energy within the metropolitan fabric.

Barriers: equity, policy gaps, and gridlock

Realising Sydney’s 75% local energy vision is technically feasible, but there are significant barriers to overcome. Chief among them is energy equity. Right now, the benefits of rooftop solar flow mostly to those who own homes or businesses and can afford the upfront investment. Renters, apartment dwellers, small businesses, and low-income households are often left out, unable to install solar on their own roofs. Any city-wide transition must ensure these groups are not left behind.

A related challenge is the current project-by-project approach – most efforts focus on individual properties, with far fewer initiatives enabling energy sharing at the community or precinct level. This is partly due to fragmented governance and policy gaps: Sydney has 33 local councils, but no single authority or clear city-wide leadership driving the renewable agenda. Without better coordination (potentially through a metropolitan energy taskforce), projects that span multiple sites or neighbourhoods face bureaucratic hurdles and unclear responsibility.

Then there are regulatory obstacles; energy rules have not kept pace with new technologies and business models. For instance, regulations often make it hard to share power between neighbours or install community batteries, because the frameworks for local energy trading or micro-grids lag behind innovation. Outdated regulations and slow approvals can stall projects that do not fit a centralised model.

Financial and technical barriers also play a role. Upfront costs for large batteries are high, and it is often unclear who should invest. For example, should it be the landlord or the tenant who pays for solar panels and battery? Such split incentives can slow uptake in the commercial/industrial sector.

Finally, building public trust and awareness is critical: communities need to understand the tangible benefits of renewable energy, such as lower bills, jobs, and reliable power – not just the environmental rationale – if they are to embrace local energy projects. Overcoming these hurdles will require targeted policies and collaboration across government, industry, and the community.

Recommendations: from buildings to city scale

To turn vision into reality, the Sydney as a Renewable Energy Zone report outlines a comprehensive set of recommendations spanning multiple scales of action. In essence, it calls for a “whole-of-city” approach, where every scale from individual buildings, neighbourhoods, and districts to greater the metropolitan region contributes to the energy transition in a coordinated way.

Why the transition is urgent

Several converging factors make this transition especially urgent for Sydney. First, coal-fired power stations are retiring, leaving a supply gap. The last coal generator in New South Wales is expected to close by 2038 under current plans. Replacing that capacity is critical to keep the lights on.

At the same time, Sydney’s energy demand is enormous and growing. It currently accounts for roughly 40–45% of NSW’s total electricity use, and this will rise further as the city’s population grows and more buses, cars, and buildings electrify. By 2030, over half of new car sales are expected to be EVs, and the entire Sydney bus fleet will be electric by 2035, adding significant load to the grid.

The impacts of climate change are also intensifying; extreme weather events, from heatwaves to storms, are putting strain on the grid and communities. Sydney has endured 12 major disaster events since 2020, and concerns about power reliability during disasters are rising; In a recent survey, residents ranked power failures as a top shock scenario for the region.

Expanding local renewable generation with storage improves resilience. For example, home batteries and even EVs can keep critical appliances running during outages, as seen when battery-backed homes kept their lights on after Queensland’s Cyclone Alfred.

And finally, NSW is not on track to meet its 2030 emissions targets, especially after 2024 marked record high temperatures. Accelerating urban clean energy is essential for closing that gap.

- Building-level actions: Implement measures to accelerate uptake of renewables on individual homes and commercial buildings. This includes mandating or incentivising solar PV on new developments, offering “solar for rentals” programs (rebates for landlords who install solar so that tenants benefit), and introducing minimum energy performance standards for rental properties.

The goal is to ensure all buildings, not just owner-occupied ones, can produce or at least access cheap solar power. Additionally, fast-tracking approval processes for home batteries and making new buildings “battery-ready” will help scale storage deployment.

- Precinct and community initiatives: Foster local energy solutions at the neighbourhood or precinct scale. The report urges support for community-owned energy projects and trials of shared infrastructure. For example, establishing more community battery systems with equitable access models so apartment residents and those without their own panels can store and use renewable electricity. It also suggests expanding virtual power plant programs with inclusive participation, allowing households without solar/batteries to still join and benefit.

Precinct-level governance and financing models will need to be developed so that shopping centres, business parks, or mixed-use districts can invest in communal solar and storage (perhaps through special purpose entities or co-ops). These efforts can turn suburbs into mini zones of energy self-sufficiency, demonstrating how power sharing at the community scale lowers costs and improves reliability.

- Metropolitan coordination: At the city/region level, the report calls for strong leadership and strategic planning to tie everything together. One important recommendation is to establish a metropolitan renewable energy roundtable, bringing state government, local councils, industry and community representatives to one table. This body would set clear goals (for equity, reliability and emissions) and align the patchwork of initiatives across Sydney’s 33 councils.

Sydney also needs a comprehensive spatial energy strategy that maps where the best opportunities are for solar, batteries, and network upgrades. Such a plan would identify which districts have enough roof space or which substations could host big batteries, guiding investment to the most impactful projects.

- Smart policy: The report poses several concrete policy initiatives. These include reviewing heritage and zoning rules that restrict solar panels in certain areas (expanding on the City of Sydney’s recent move to allow panels in historic districts), mandating solar PV on suitable new buildings and streamlining battery approvals to accelerate deployment, and create regulatory sandboxes to allow peer-to-peer energy sharing and microgrid trials within urban areas.

Finally, looking ahead, the report highlights the need to integrate end-of-life planning for all this new infrastructure – establishing programs to recycle or repurpose solar panels and batteries so that today’s solution does not become tomorrow’s waste problem.

As Sydney moves from vision to build-out, we are keen to hear from HVAC&R professionals who are piloting the next wave of rooftop, battery or community-scale solutions. Together we can turn every suburb into part of the grid of the future.

About the author

Muhammad Ali, M.AIRAH, is the National Discipline Lead – Energy Advisory at Arcadis Australia Pacific. He co-authored the Sydney as a Renewable Energy Zone report, which was published by the Committee for Sydney in June 2025, in collaboration with Arcadis and Arup.

You can access the full report for free via this link.

This article appears in Ecolibrium’s Spring 2025 edition

View the archive of previous editions

Latest edition

See everything from the latest edition of Ecolibrium, AIRAH’s official journal.