Peter Phillips, F.AIRAH

Member ASHRAE (Ret), Fellow AIRAH (Ret)

ABSTRACT

Delivering successful, high-quality, sustainable, future-proofed, built-form projects requires planning and coordination of complementary factors. This includes broad-based statements and detailed expression of community and project definitions of sustainability objectives. The paper suggests some of the factors necessary to deliver a responsible, sustainable, built-form outcome.

INTRODUCTION

Throughout our working lives we develop skills to deliver all types of projects. Accumulated experience delivers value. This paper contemplates frameworks that may be encountered in delivering successful, high-quality, sustainable, future-proofed, built-form projects

Defining Quality

What is quality for the built form? Quality is the body of work (project) that fulfills a concept and its objectives. It incorporates three things: an aesthetic, a resilience, and a utility.

Aspirations of quality

There is nothing more satisfying than delivering a project, on time and on budget. Enjoying relationships built along a journey of discovery and delivery can create long-lasting bonds of mutual satisfaction and an eagerness to explore not just the current project phase but also an opportunity to participate in the next project.

Quality can be compromised through under-explored assessments of risk and reward, authority and responsibility. When quality is compromised, so too is satisfaction and enjoyment of the project journey.

Striving for quality

What is quality to project participants? Quality may be about a responsibility to evaluate and enhance one’s ability, knowledge, reputation and commitment to collaborate within a collective. Perhaps quality is an obligation to achieving a successful conclusion to a concept and its objective. Or perhaps it is an expression of observations of a discerning user. Maybe quality depends on the creation and adoption of processes that reflect issues of importance in terms of time and cost.

According to ISO standards, “Sustained success is achieved when an organisation attracts and retains the confidence of customers and other interested parties. Every aspect of customer interaction provides an opportunity to create more value for the customer. Understanding current and future needs of customers and other interested parties contributes to sustained success of the organisation.” Reference 1

ISO quality management standards are based on seven quality management principles: “Customer focus, leadership, engagement of people, process approach, improvement, evidence-based decision making and relationship management”.

So, to achieve quality, a project team should be in tune with a journey towards achieving concept and objectives, within the broader community’s understanding of the importance of sustainability, and within an organised process of creation and review.

Project Commencement

A project initiator presents ideas to project participants. Information transference evolves into a description of, “What, why, how, when and by whom” (concept, objective, framework, program, team). Often this expression of project is referred to as the “project charter”.

“A project charter is a formal, typically short document that describes your project in its entirety – including what the objectives are, how it will be carried out, and who the stakeholders are. It is a crucial ingredient in planning the project because it is used throughout the project lifecycle.” Reference 2

To create a fulfilling project, every individual working on the project should ascribe to the imperatives that stakeholders share within the project charter. The charter should be maintained as a living document and be frequently consulted and discussed.

Leadership

It could be said that the most important individual within a project team is the one assessing the capacity of the team to succeed. It is a critical role. An important part of this is reviewing not just what is being represented, but also what has not been considered. Small issues of gap or potential conflict can have far-reaching consequences in time, cost and quality.

How often have under-explored assessments of risk and reward, authority and responsibility, and capability and capacity been in conflict with a project’s concept and objective statements?

We often refer to the collaborative depicter of “1+1=3”, but when does 1+1 not equal 3? Often it is when the “+1” is associated with a negative influencer. The result of this negative influence can work against achieving a project’s concept and objective, as well as impacting negatively on time and costs.

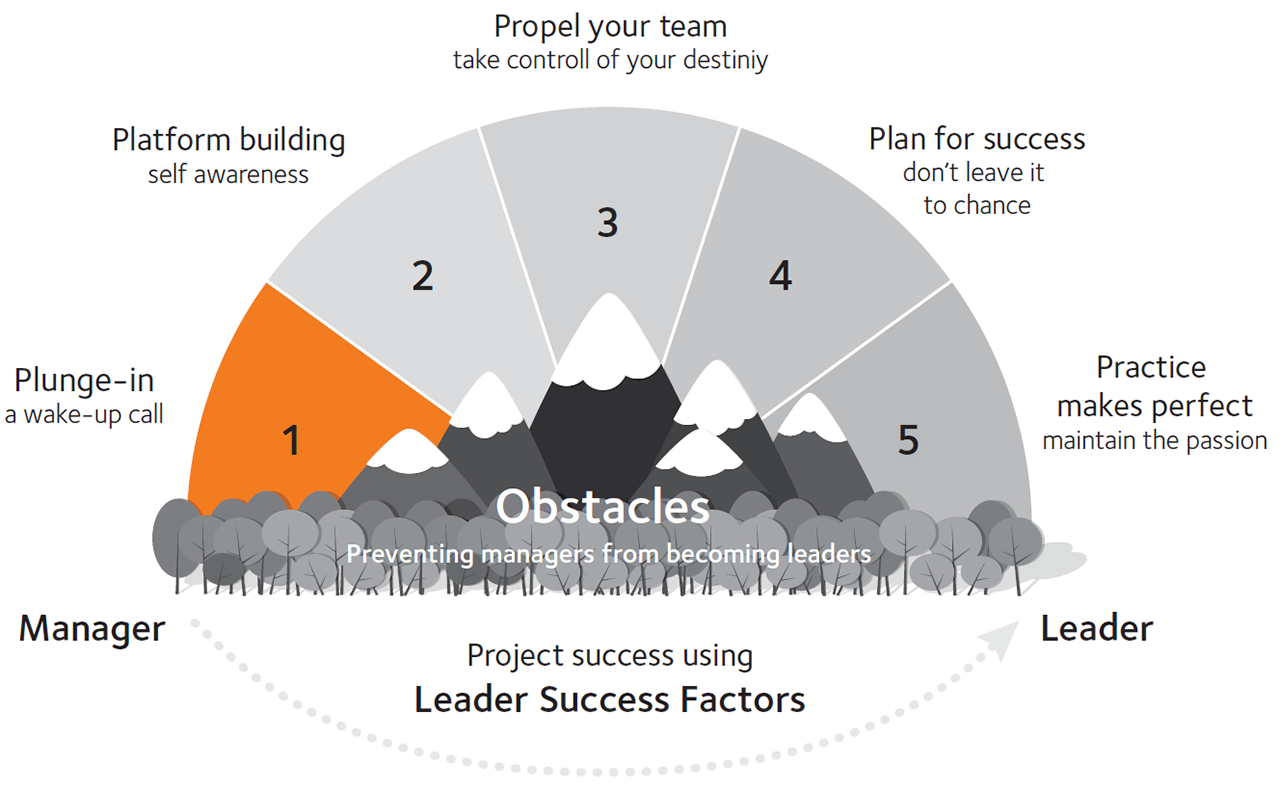

So, perhaps project success (quality) can be driven from a framework of improvement of self and situation awareness. Figure 1 Reference 3 depicts a potential pathway for progression from manager to leader.

It should not matter whether you are managing projects, situations, or self, becoming a leader is part of a journey of accumulating beneficial skills and working through tensions to achieve a collaborative outcome.

Figure 1: Example framework, leader success factors

Developing quality objectives

Perhaps the most important aspect of delivering quality is assessing and acquiring competency towards achieving a project’s stated and assumed objectives. Developing a framework of sub-concepts will not only help guide oneself, but also act as a prompter towards sharing responsibilities of cooperation with others.

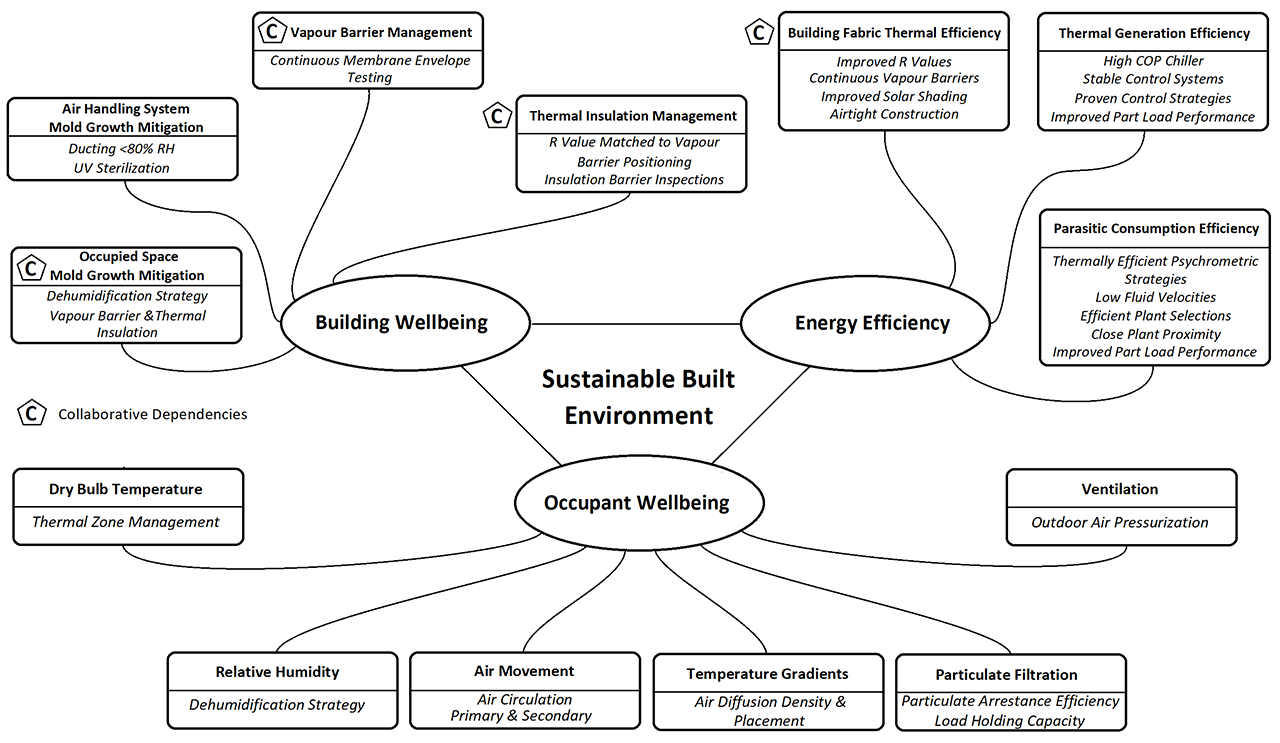

Figure 2 suggests a non-exhaustive HVAC framework, indicating facets of design to be strategised towards delivering upon a project objective.

The objective to be delivered could be, “An environmentally sustainable comfort air conditioning solution incorporating a mold mitigation strategy”. Indicated are several collaboration dependencies where other designers share responsibility to deliver upon the objective.

A leader in the field of HVAC design would initiate and monitor resourcing to deliver upon HVAC-associated responsibilities and be a firm manager ensuring that other designers, documenters and constructors deliver upon known shared responsibilities. A novice HVAC design manager may understate shared responsibilities, thereby leading to tension in delivering a stated objective.

Figure 2: Example framework, facets of design.

SUSTAINABILITY FRAMEWORK

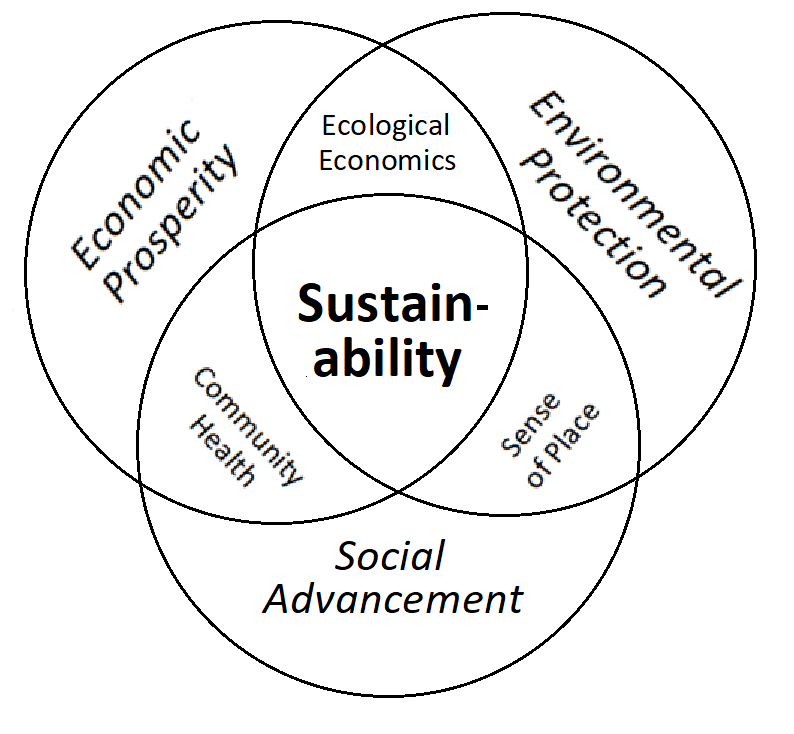

The word “sustainability” is often overused and misunderstood. An under-developed assumption of what sustainability means can lead to initiatives that deflect the project away from a community-opinion-based and responsible conclusion. A project’s sustainability credentials should be developed through stakeholder engagement.

Stakeholders, with a broad array of skills, can be used to expand definitions of sustainability for incorporation into the project charter. Figure 3 Reference 4 expresses primary and secondary considerations associated with a concept of sustainability.

Detailing secondary and tertiary statements of sustainability within a project charter can assist designers, documenters, constructors and reviewers to achieve the greatest value for future generations of project users. An example of this could be development of the circle of economic prosperity to incorporate, “A built form design life objective of 100 years …. incorporating mold mitigation strategies”. Notions of sustainability can be developed into descriptions of a project objective for designers to strategise and deliver.

Figure 3: Example framework, sustainability strategy.

Contracts

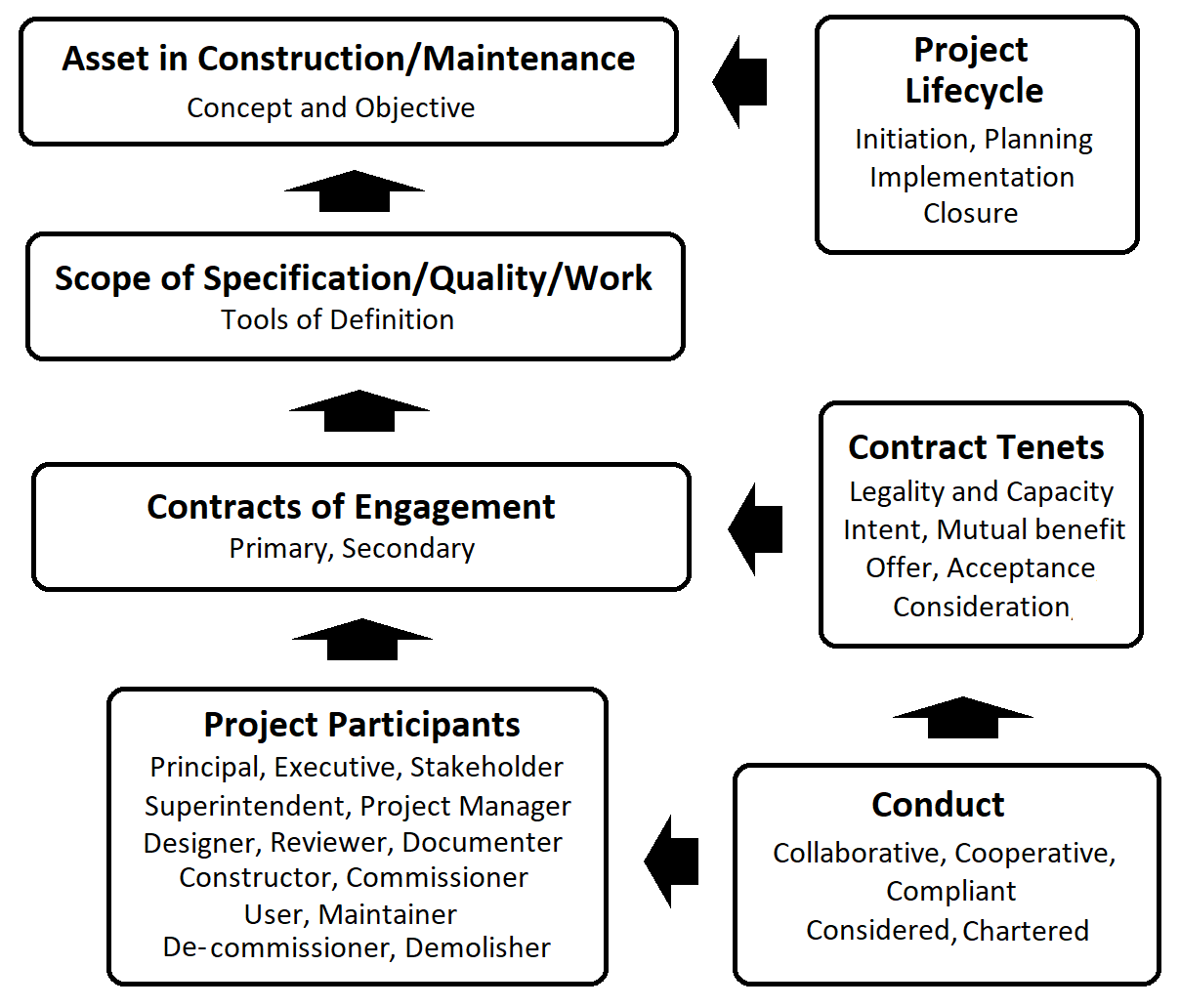

Establishing and maintaining a built-form fixed asset will likely be managed within several contracts. Multiple contracts initiated by the Principal may be executed in conjunction or sequentially. Understanding responsibilities within the establishment and passage of contracts is important for those executing primary or secondary roles.

Figure 4 suggests a framework where the tenets of contract potentially fit within a built-form project.

Perhaps the least understood contract tenet is the test of mutual benefit, particularly as it applies to changes to the contracted “scope of work” depiction. Unfortunately, often the least developed and less understood information shared in cost-driven projects is the development and sharing of a contract’s concept and objective.

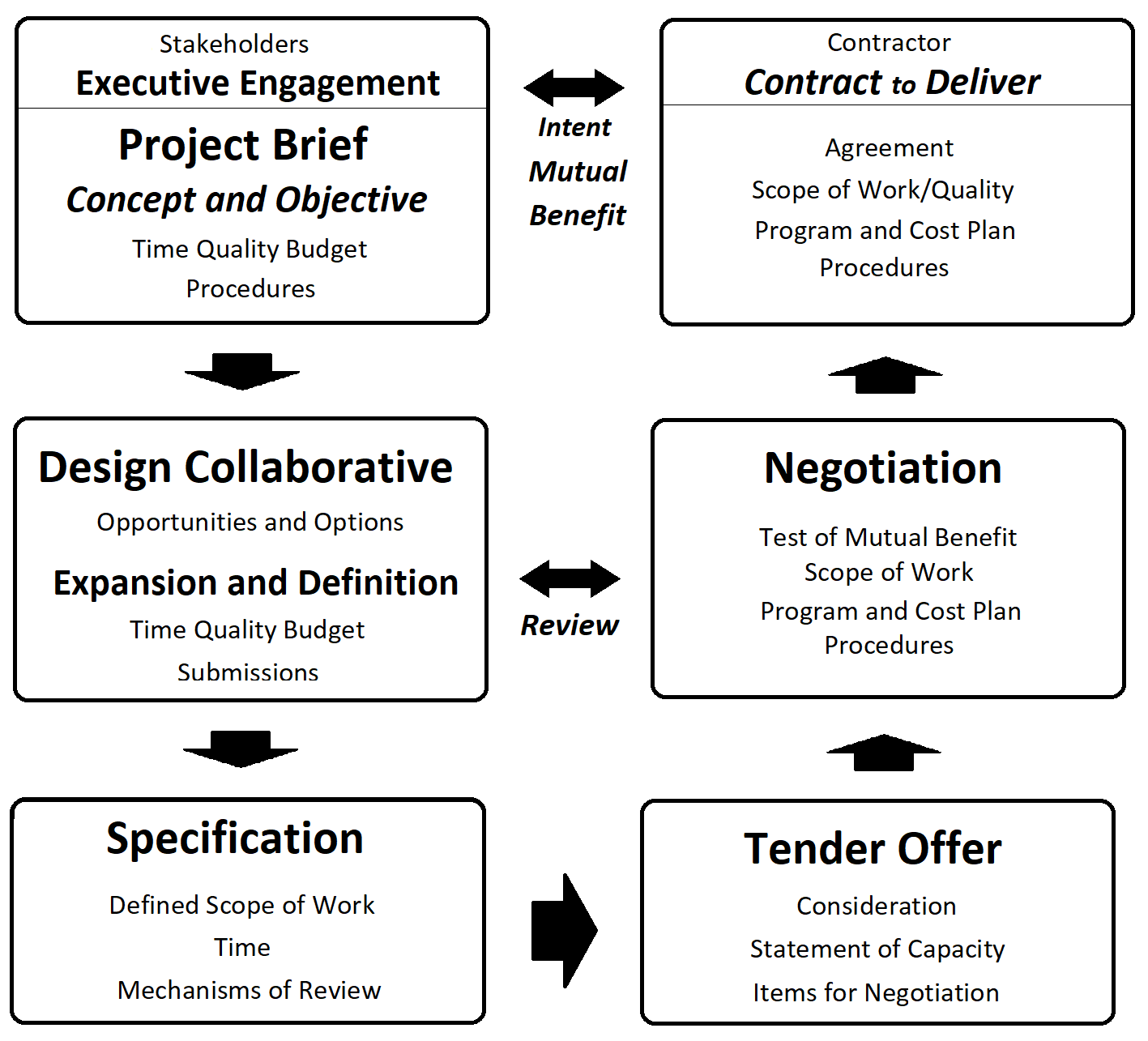

Delivering a project, or multiple contracts within a project, requires a framework of pathways and success strategies. Figure 5 suggests a framework of “activities and flow” towards the formulation of a detailed project program.

Figure 4: Example framework, understanding contract tenets.

Figure 5: Example framework, Project contract delivery.

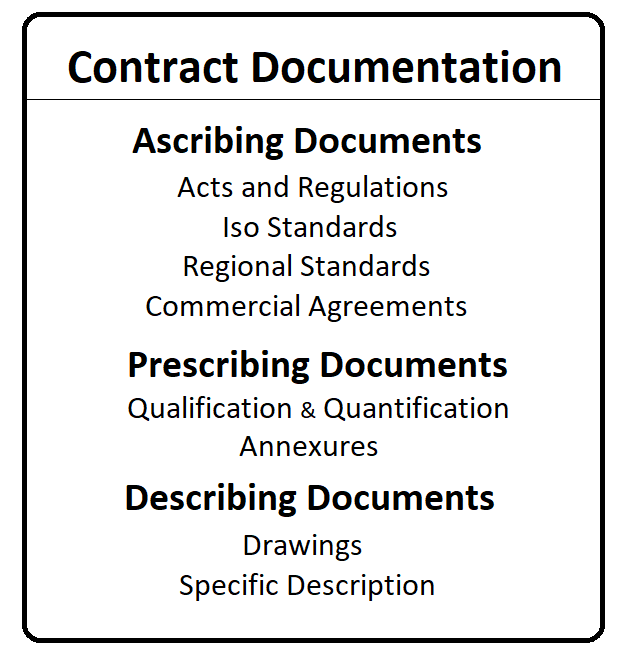

ASCRIBE, PRESCRIBE AND DESCRIBE

Built-form construction contracts usually incorporate drawings to describe a project’s physical attributes. But in those same contracts, what mechanisms define the level of quality to be delivered? Often generic documents are used to support implied characteristics of construction. Referencing Parliamentary Acts and Regulations, Iso Standards, regional standards and Articles of commercial agreement ascribe generalisations of quality to be delivered.

Many referenced documents incorporate qualifying and quantification clauses to define the parameters of deliverable quality. Defining a detail or level of success requires a specific description of the quality of work to be delivered.

At each step in project delivery, affirming and deliberate expression of the scope of contractual obligation must

be used. Figure 6 suggests a framework of contract document types.

Figure 6: Example framework, contract supportive documents.

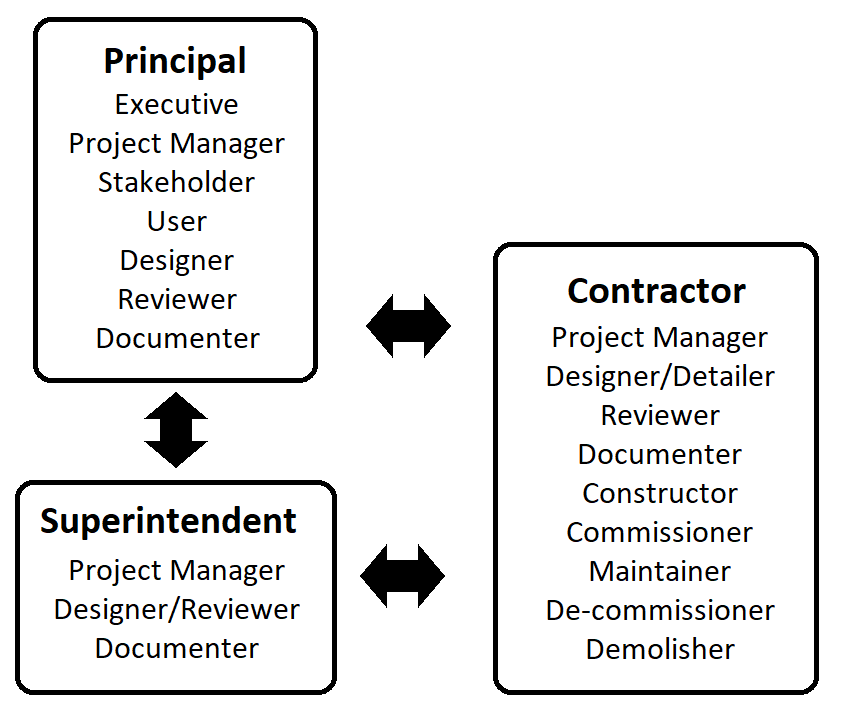

PARTICIPATORY RELATIONSHIPS

Roles that individuals play within the bounds of contract responsibility must be recognised and satisfied towards development of an “efficient completion” of contract. The three primary roles in contract delivery are: the Principal, the Contractor and the Superintendent.

Figure 7 suggests a framework of contract relationships. Effective communication within and between roles is essential for the effective progression of contracts.

Figure 7: Example framework, contract relationships.

Quality Review

The contract Superintendent’s role and responsibility is often understated and/or misunderstood. “The Superintendent primarily administers the contract, including overseeing day-to-day operations, attending meetings to ensure project aims are being met, and making decisions on variables that arise under the contract. The Superintendent’s role under a construction contract, therefore, is two-fold. The Principal appoints the superintendent as its agent and to also act as a certifier.”Reference 5

The Superintendent deliberates over whether the contract has been delivered on time, on budget and to

specification. This means that the Superintendent needs to be intimately involved with administration of the project charter, and be a counsellor of project participants where inconsistencies may arise.

Competency Resourcing

The most important resource to build is a project’s intellectual capacity. To achieve this, adoption of a framework of competency development should be purposeful and deliberate. Investment in the development of intellectual capacity of people, or of a corporate entity, or project personnel enhances capability, capacity and confidence.

Investment in core skills, inter-disciplinary skills, and relationship-bonding strategies adds value to the processes of collaboration. Skilled people with a broad understanding of other participants’ roles and responsibilities contribute to the development of sustaining pathways. Use of in-house and project-based training, with support from both academic and professionally based organisations, needs to be encouraged, to build competency beyond the skills initially acquired through core community educational programs.

There are several organisations that have developed many valuable guidance resources, including for example, discipline design frameworks and project management frameworks.

For building services designers, ASHRAE has many standards, guidelines and technical resources to support design practice. (www.ashrae.org/technical-resources/bookstore/ashrae-digital-collections)

A go-to reference for project managers is the Project Management Institute’s, A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide) – Seventh Edition and The Standard for Project Management, 2021. (www.pmi.org/pmbok-guide-standards/foundational/PMBOK)

Conclusion

When charged with the responsibility of delivering a “sustainable built-form future”, an understanding of the frameworks of establishing and delivering quality is essential. Quality incorporates aesthetics, resilience and a utilisation opportunity. Quality is about developing and delivering abilities to evaluate and enhance situation, knowledge, competency and commitment within a collective.

Every project needs active leadership participation. It should not matter whether managing projects, situations, or self, becoming a leader is part of the journey of accumulating beneficial skills and amassing an ability to deliver upon a project concept and its objective.

The creation, maintenance and sharing of a charter, and detailing a project’s concept and objectives, is essential to recognising and delivering quality. Project personnel should develop their own framework of objectives, consistent with the project charter, to move through project phases, not only to help guide oneself, but also to act as a prompter toward sharing responsibilities of cooperation with others. This includes the collective framework of sustainability, developed through stakeholder engagement and effective decision making.

Delivering a project is often managed through the establishment of multiple contracts. Expressing pathways and success strategies within frameworks of shared understanding and agreement set the scene for the development and maintenance of benefit for all. Effective descriptions and depictions of the project’s scope of work is required for the definition of quality. Many generic documents exist to aid the development and summation of project scope and responsibility.

Figure 8 expresses relationships required to deliver quality. People’s roles and responsibilities and authority must be recognised, satisfied and respected, to achieve efficient delivery of a project’s objectives.

Figure 8: Example framework, relationships toward delivering quality.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Peter Phillips is a retired building services consultant living in Tasmania, Australia

References

| [1] | Quality Management Principal, Edition 2, 2015, International Organization for Standardization www.iso.org/publication/PUB100080.html |

| [2] | Project Management Guide, Wrike Inc www.wrike.com/project-management-guide/faq/what-is-a-project-charter-in-project-management/ |

| [3] | Project Success Through Leadership: How a Technical Manager Transitions Into a Highly Effective Leader, 2015, Jenkins, (https://trihelix.com.au/) |

| [4] | The Western Australian State Sustainability Strategy: Is change happening? 2003, Newman https://researchrepository.murdoch.edu.au/21611/1/WA_State_Sustainability_Strategy.pdf |

| [5] | What is the Role of a Superintendent? Roberts, https://legalvision.com.au/what-is-the-role-of-the-superintendent/ |

Acknowledgments

Thank you, David Chin and Piers Horwood, who shared their anxieties, suggesting that delivering quality projects was at risk.